Video games have come a long way in a short time. When I was a young nerd in the nineties, most games had only one option of player character. He was usually male, with a few exceptions. “Pokémon Crystal,” released to the West in 2001, was the first of its series to offer a female option. While representation of women in gaming is still lacking, something came from nothing in just a few years. The industry evolves rapidly, so player characters may soon be beyond male or female.

Despite that progress, most games remain stuck at the same intersection of two bathroom doors. In games where the player creates their avatar, they must choose to be either male or female. Identifying their gender is one of the first choices a player makes after their name, and they cannot opt out. “The Elder Scrolls: Skyrim,” the “Mass Effect” series and the most recent “Pokémon” games all require the player to choose between male or female.

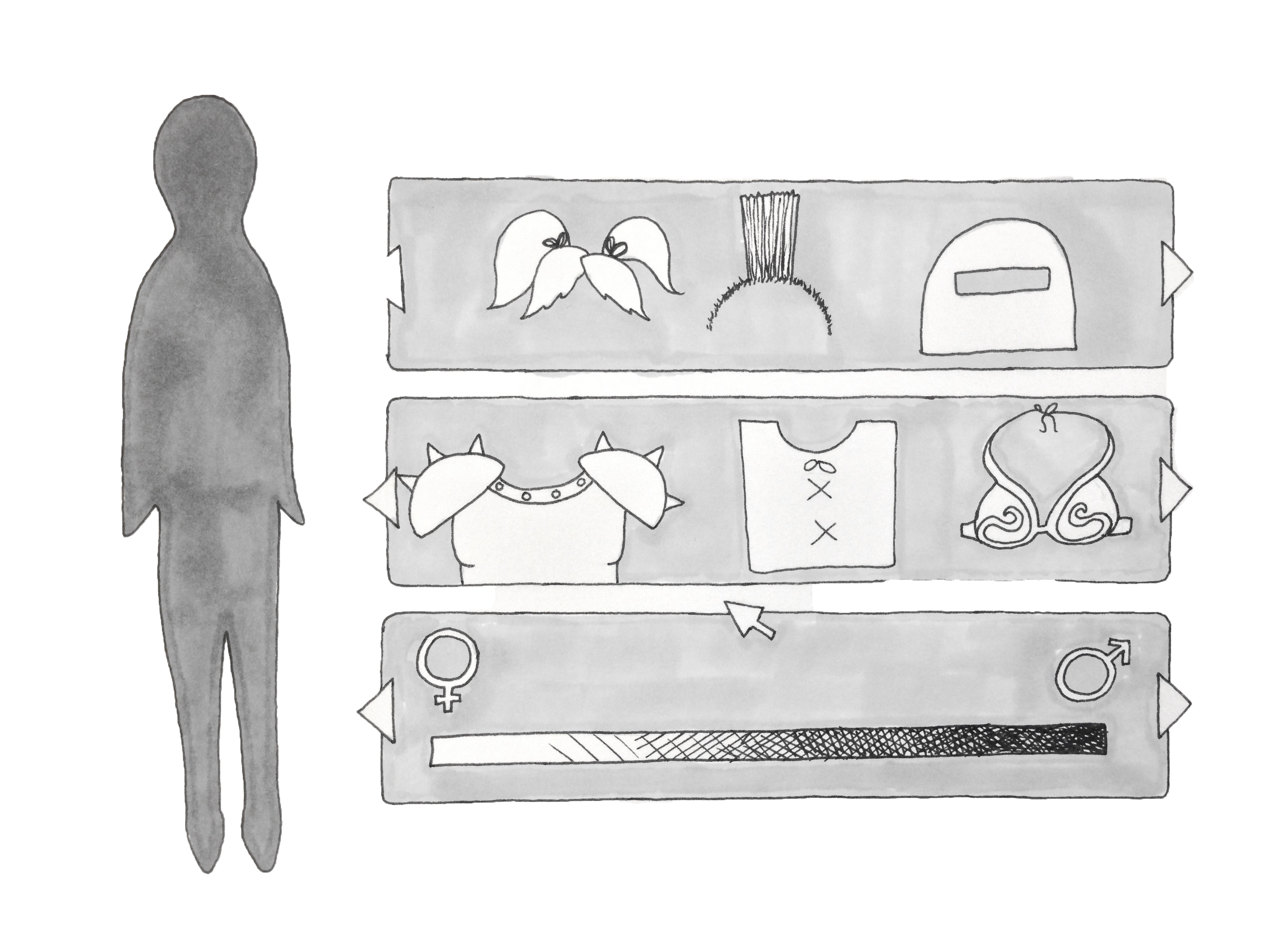

However, this question of gender is unnecessary. The above-mentioned games all feature extensive character creation. Hair color, eye color, nose shape and, occasionally, species are all up to the player. Why, then, are there only two choices for gender?

Adding more choices is not necessarily the solution. Someone is still left out. Rather, removing the choice and the binary altogether may be the best resolution.

With the character-creators many games have, adding gender is redundant when the player can just make their avatar look as masculine or feminine as they please. “The End” is a browser game where the player platforms and puzzles through the afterlife. They also get to create their own avatar without specifying a gender. Creating a very masculine or feminine avatar is easy, but there is no prompt to define them as either male or female.

Players who identify as either male or female will not miss the question, and players who prefer neither will appreciate the absence of the binary choice. In the case of non-human characters, this issue is much simpler. Some of the available characters in “Super Smash Bros.” provide non-obviously gendered alternatives to the gendered humanoid characters. Pikachu and Kirby, for example, are both technically male in their respective series, but the casual player would not be able to tell from the character-select screen. Also, Kirby is a fluffy pink ball with a permanent blush. He does not easily fit into any human category of gender. His non-humanoid nature makes him beyond gender. He still uses masculine pronouns, but nothing about Kirby himself informs the viewer of his gender.

While gender-neutral avatars certainly have their uses, by no means does every video game need them. Player-created avatars are a blank slate for the player to make up their own story. Often, the most effective stories grow out of pre-existing characters. However, these characters are usually white males who never vocalize any distress over their gender.

“Gone Home” is a recent indie game to focus more closely on ideas of gender and sexuality. It’s a theme few games wish to grapple with, but the critical success of “Gone Home” suggests more games may follow suit in the near future. Most will probably be by indie developers, but this is an issue that’s going to take a very long time to become mainstream.

Currently, sexism and homophobia are major issues in the video game community, but video games are also the only medium that allows its audience to become completely immersed in the life and experiences of another person.

That sympathy may prove a powerful tool for change. Video games may have an easier time adapting gender neutrality than other forms of media because gender is less permanent in games than in film, television or literature. The medium also has the ability to evolve much faster to conform to new norms.

Please direct any comments about this article to lawrentian@lawrence.edu