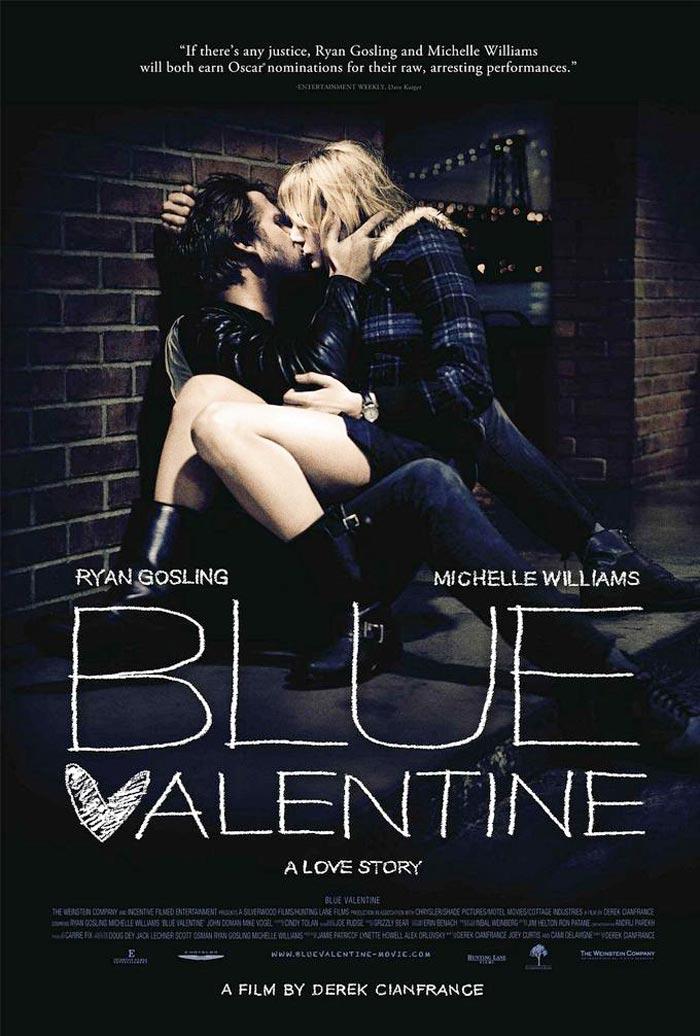

(Image courtesy of the Weinstein Company)

When filmmaker Derek Cianfrance first conceived of “Blue Valentine” nearly a decade ago, I’m sure he did not imagine the difficulties he would face in bringing the project to the big screen. To begin with, he couldn’t obtain the proper backing from any studio and secure the money necessary to produce the film.

After finally obtaining the money nearly eight years later, the production was halted after the sudden death of Heath Ledger, the ex of star Michelle Williams. Instead of recasting, Cianfrance chose to stick with Williams, the only actress that he wanted for that role.

When the film was finally released, it received an NC-17 rating because the male protagonist, Dean (Ryan Gosling), performs an explicit sexual act on Williams’ character, Cindy. The rating spurred much controversy as both stars released statements referring to the decision as misogynistic in nature.

Gosling said, “The MPAA is okay supporting scenes that portray women in scenarios of sexual torture […] for entertainment purposes, but they’re trying to force us to look away from a scene that shows a woman in a sexual scenario, which is both complicit and complex.”

Needless to say, the rating was overturned. While the NC-17 rating was clearly an unfounded decision, it did help the film garner buzz.

“Blue Valentine” tells the story of the relationship and subsequent struggling marriage of Dean and Cindy. On the surface, the film may look like any drama focusing on the dissolution of a marriage: Dean drinks too much and Cindy is more focused on her career as a nurse than her relationship.

The only thing keeping them together is their daughter, Frankie, and divorce seems inevitable. Dean decides that the only way that they can save their marriage is to book a motel room, get drunk and have sex. Cindy is not initially interested, but she gives in to Dean’s request.

The film really breaks away from other generic films in its narrative framework. Cianfrance contrasts the ending of Dean and Cindy’s marriage to the beginning of their relationship through a series of flashbacks. This contrast is surely a manipulative tool to make the viewer feel more for these characters, but it works. And it works well.

In the flashbacks, Dean and Cindy are both young and full of energy and optimism. In the present, though, Dean is balding, overweight and paints houses for a living, which, according to Cindy, squanders his potential. The physical difference in Dean is enough to tell the viewer that his life has not turned out as well as it may have seemed from the past.

Cianfrance also utilizes different cameras for the two time periods, and the difference in quality further separates the past from the present. The flashbacks have a much more amateurish feel to them, which relates to the youth of the characters and their potential — an idea that is revisited in the film.

The musical score, performed by the Brooklyn-based band Grizzly Bear, fits the film perfectly. The majority of the songs are instrumental, and they work very effectively to chronicle the dissolution of Dean and Cindy’s marriage.

“Blue Valentine” is easily one of the best films released in 2010, even though it received only one Academy Award Nomination — Michelle Williams for Best Actress. The film marks Gosling’s return to the screen after a three-year absence. His performance, I believe, was even stronger than Williams’, and reaffirms his status as one of the best up-and-coming actors in Hollywood.

Put simply, “Blue Valentine” is a must see. Cianfrance’s long wait to get his film to the big screen was worth it, and he is a director to keep an eye on.