The opinions expressed in The Lawrentian are those of the students, faculty and community members who wrote them. The Lawrentian does not endorse any opinions piece except for the staff editorial, which represents a majority of the editorial board. The Lawrentian welcomes everyone to submit their own opinions. For the full editorial policy and parameters for submitting articles, please refer to the about section.

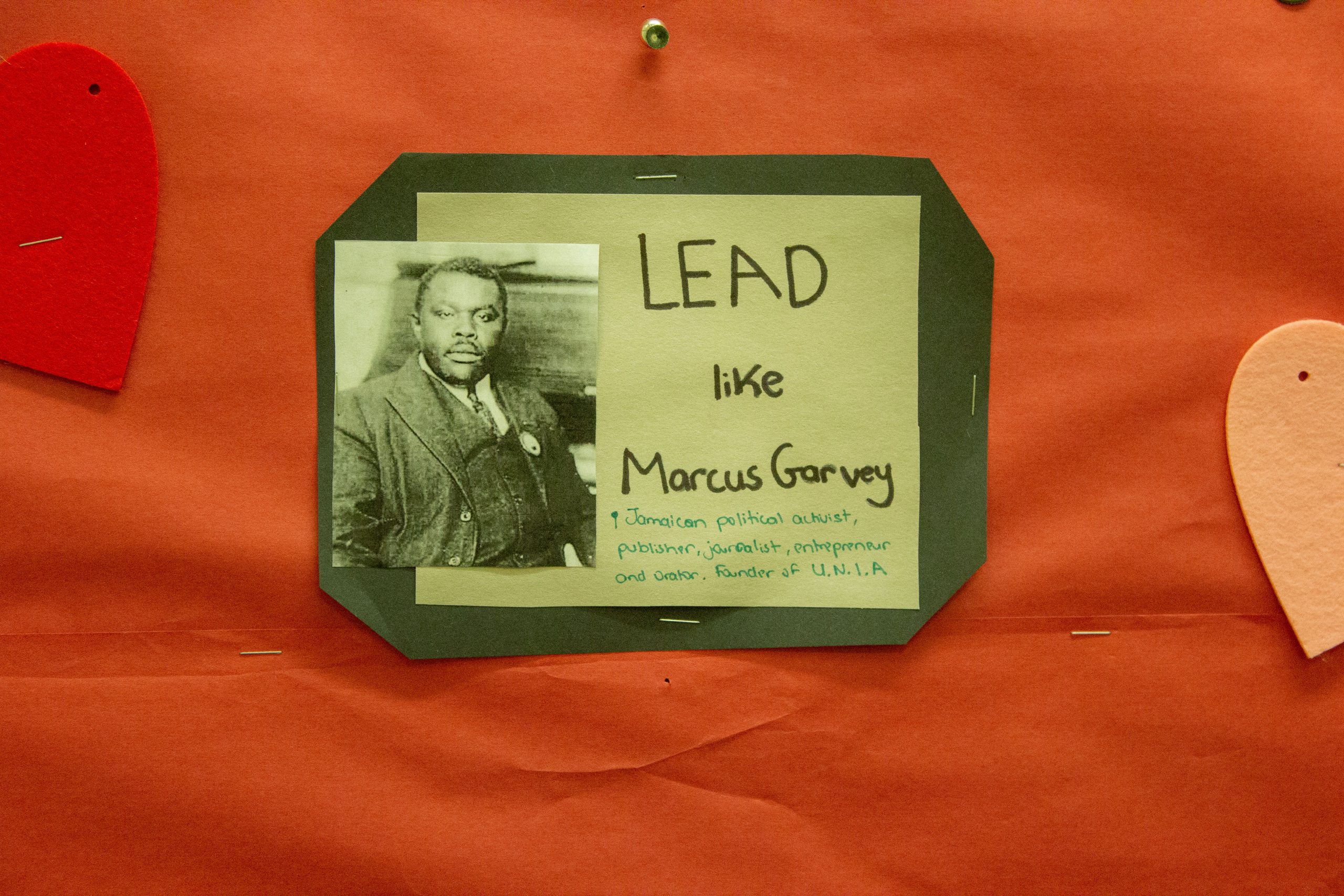

February is Black History Month, a time to celebrate and learn about the history of the Black community. For this celebration, I recently noticed on a board filled with African American activists to look up to in Trever Hall. Looking at some of the names, curious about some historical figures that would be put on the board, I saw one person who stood out from the rest: Marcus Garvey, the founder of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). The reason that this person stood out was because Marcus Garvey was a man who openly claimed fascism to be his invention and worked with the Klu Klux Klan (KKK). He is not a man to be admired or looked up to.

Marcus Garvey is a controversial figure today, and was a controversial figure during his days of activism too. Although he was at first received very well within the budding civil rights community, especially during the early years of the Harlem Renaissance, he very soon became split from the community due to some of his more reprehensible beliefs. A. Philip Randolph, the person who provided Garvey with his first audience, would later denounce him and regret platforming him. Garvey believed that segregation was a good thing. He actively worked with the KKK and was notably amicable with Edward Young Clarke, the grand wizard of the KKK from 1915 to 1922, stating that he and the KKK shared the common goal of “the purification of the races, their autonomous separation and the unbridled freedom of self-development and self-expression. Those who are against this are enemies of both races, and rebels against morality, nature and God.”

On top of wanting all races separated from each other, Garvey was also quite antisemitic. During his 1923 trial for mail fraud, Garvey would blame Jewish people for being biased against him during the trial due to his connections with the KKK, even calling the judge and District Attorney “damned dirty Jews.” In 1928 Garvey told a journalist, “When they wanted to get me they had a Jewish judge try me, and a Jewish prosecutor. I would have been freed but two Jews on the jury held out against me ten hours and succeeded in convicting me, whereupon the Jewish judge gave me the maximum penalty.”

Marcus Garvey also held disdain for people of mixed-race backgrounds. Garvey was vehemently against interracial relationships and the existence of mixed-race individuals. He believed that racial purity was particularly important to maintain the Black identity, and that mixed race people would always become “race traitors.” He stated that the UNIA stands for “the pride and purity of race. We believe that the white race should uphold its racial pride and perpetuate itself, and we also believe that the Black race should do likewise. We believe that there is room enough in the world for the various race groups to grow and develop by themselves without seeking to destroy the Creator’s plan by the constant introduction of mongrel types.”

As a result, many African American civil rights activists despised Marcus Garvey, culminating in the “Garvey Must Go” campaign. The “Garvey Must Go” campaign was started by African American activists who were opposed to Marcus Garvey’s approach and wanted to see him stop his activities. The movement got a massive boost in support after Garvey remarked in a speech in New Orleans that “Black people had not built the railroad system; they should not insist on riding in the same cars with white patrons.”

W.E.B. Du Bois, a very prominent civil rights activist, professor of history and sociology, and one of the founders of the NAACP also despised Garvey; in fact, they were known to hate each other. Du Bois took issue with much of the same problematic behavior that Randolph did, but he also disagreed with Garvey on another important point: Garvey’s staunch anti-socialist sentiments. This distanced Garvey from the growing socialist movement during the early 1900s that was popular amongst labor organizers and civil rights activists of the time. Marcus Garvey’s anti-communism and racist beliefs eventually led him to fascism. Garvey even claimed that Benito Mussolini copied his model of fascism in an interview with historian J.A. Rogers: “We were the first Fascists, when we had 100,000 disciplined men, and were training children, Mussolini was still an unknown. Mussolini copied our Fascism.” In the same interview, he also said that “Mussolini copied Fascism from me, but the Negro reactionaries sabotaged it”.

Garvey had ambitions of forming a single party, totalitarian Christian ethno-state to rule over all of Africa, with Garvey at the top with absolute authority. Historian and professor Willson Jeramiah Moses described Garvey’s vison of this African state with words such as “authoritarian,” “racist” and “elitist.” Many would also go onto point our Garvey’s severe ignorance surrounding the African continent broadly. He believed in many stereotypes about Africa and the native African peoples: one of his goals in Africa was “to assist in civilizing the backward tribes of Africa,” and another was to “promote a conscientious Christian worship among them.” Garvey also had his own secret police in the form of the African Legion, a group of people who would march in parades and would gather surveillance on members. W.E.B Du Bois wrote an article condemning Garvey after followers of Garvey murdered Reverend James Eason, an exiled senior member of the UNIA. Garvey responded by calling Du Bois an “unfortunate mulatto who bewails every drop of Negro blood in his veins.”

With such a wealth of Black activists to look up to and imitate, it’s clear that instead of Garvey, we should admire other Black historical figures such as W.E.B. Du Bois, or A. Philip Randolph, the two aforementioned civil rights activists and labor advocates. W.E.B. Du Bois was himself a Pan-Africanist, like Marcus Garvey, though he had different opinions on the subject. His book, “The Souls of Black Folk,” is an excellent read that I highly recommend. A. Philip Randolph is very much unknown in a lot of today’s discourse. Randolph was responsible for some of the first ever Black labor union organizing. He also was instrumental in organizing the march on Washington in 1941 and in 1963, where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his now iconic speech. If you’re looking for a Black activist from outside of America, you may be interested in learning about Frantz Fanon, a psychiatrist, philosopher and Pan-Africanist who was interested in the psychopathology of colonization and various concepts surrounding decolonialization. He wrote a book called “The Wretched of the Earth” which is another great read that I would highly suggest to readers hoping to learn more about Black history.