Senior Matvei Mozhaev’s art exhibition, “Reversing a Palimpsest: Spiraling of Soviet Modernity Through Yebenya Aesthetics,” was featured in the Mudd Gallery from Monday, May 1 to Tuesday, May 9. It explored the past century of Russian sociocultural, environmental and political history through a captivating blend of visual art, academic research and personal testimonies.

The exhibition’s title describes the revival of Soviet symbols, law and ideology in contemporary Russia. The word “palimpsest” refers to a manuscript that still contains traces of old writing, despite efforts to erase it and cover it with new words. Mozhaev summarized the exhibition as “an analysis of the fragmented resurrection of Soviet power structures in contemporary Russia through an artistic movement that depicts the everyday living environment.”

The exhibit deconstructed these topics through yebenya, an aesthetic centered around the irregular juxtaposition of multiple historical eras. Although it shares some similarities with Western urban decay aesthetics, yebenya focuses specifically on architectural and social decay in post-Soviet countries.

“Yebenya just means a place that is undesirable to live in because it is not meeting Western modernization standards in some way,” Mozhaev explained.

Mozhaev started sharing yebenya aesthetics with the Lawrence community last fall, when he developed a presentation on yebenya aesthetics for his job as a student language assistant for the Russian academic department. He also drew inspiration from an art history class on artistic portrayals of ruins, as well as his own childhood in Russia.

“I grew up in a small town about 30 minutes away from Moscow, which was filled with a lot of the things you can find in yebenya aesthetics,” said Mozhaev. “We lived in this small five-story apartment building that was probably built in the 1970s, or maybe even earlier. I think there was always this childhood connection that really sprung the initial interest.”

Recordings of two interviews—one with Mozhaev’s father, Aleksander, and another with Associate Professor of Russian Peter John Thomas—added an auditory component to the gallery. According to Mozhaev, the interview with his father provided a deeply personal perspective, whereas Thomas’s analysis was grounded in historical facts. In addition to Thomas, Mozhaev credited Lawrence professors Beth Zinsli, Nancy Lin and Ameya Balsekar for contributing ideas to his exhibition.

For Mozhaev, yebenya has also played a major role in his understanding of the war in Ukraine and society’s reaction to current politics in Russia. One of the exhibition’s central foci is the sociopolitical complacency and stagnation in modern Russia, particularly in regard to the war in Ukraine. While public opposition to the war does exist, Mozhaev argues that resistance has been limited because Russia’s turbulent political history has created a widespread culture of indifference towards politics.

“There is really no simple way to explain why [the war] happened,” he said. “I think we’re continuing to really make sense of it as it goes on. For me, it’s still very overwhelming. I cannot imagine myself living in Russia right now, because there are so many factors there that move people towards committing certain choices.”

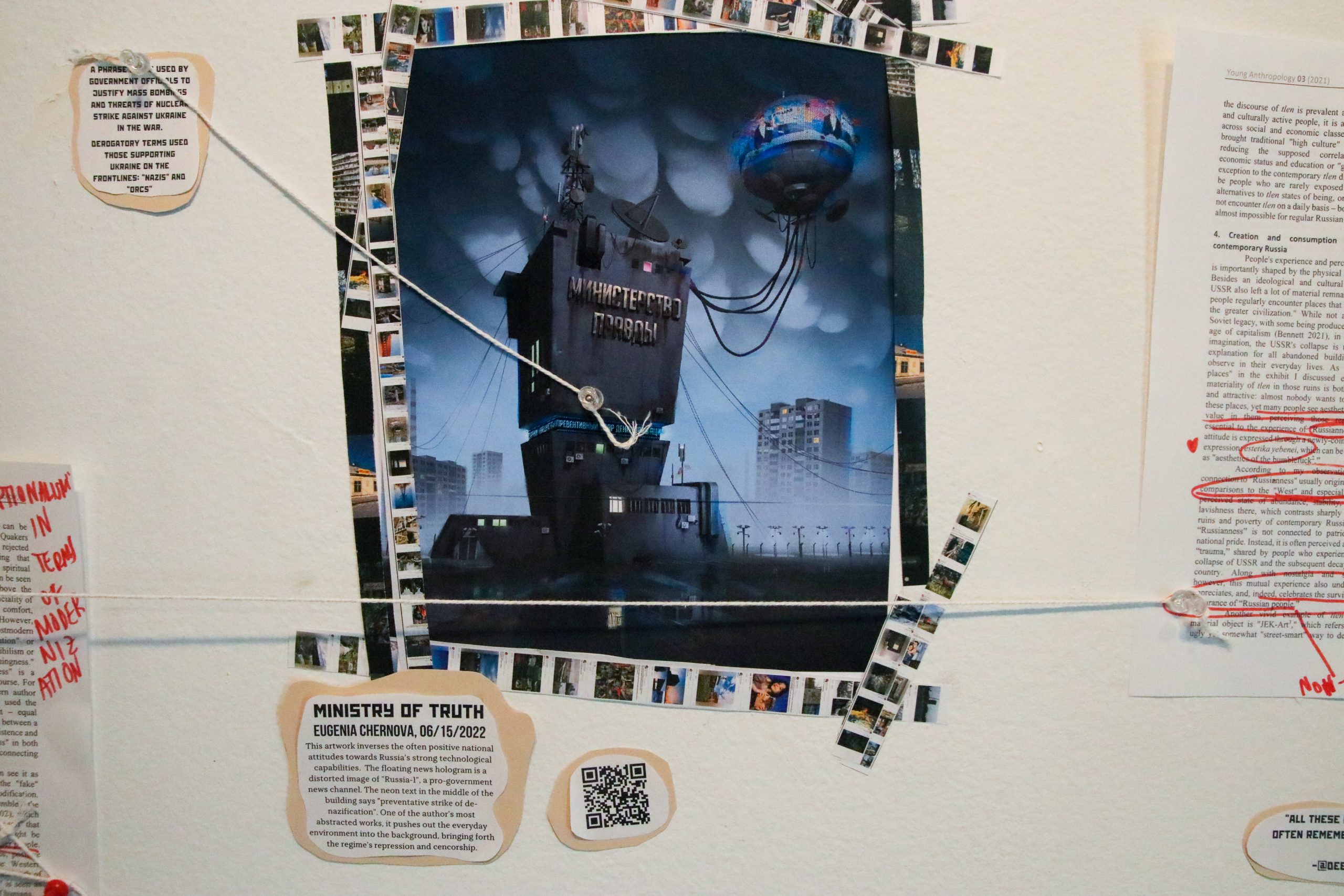

The exhibit’s walls were lined with visual art and interviews from contemporary Russian artists Eugenia Chernova, Fedor Titov and Andrei Bogolyubov. Chernova’s works openly criticize the war in Ukraine and the Russian government’s use of suppression and propaganda, whereas Titov conveys a more general sense of distress without explicitly mentioning the war. Bogolyubov’s works, including the idyllic wintry scene of brutalist apartments projected against the gallery’s back wall, capture Soviet nostalgia.

Mozhaev also incorporated an idea web of academic articles about Russian history, mostly from Western perspectives, to provide additional historical context. Strings crisscrossed the gallery, demonstrating surprising connections between themes across the gallery. Mozhaev’s handwritten notes filled the margins of each paper, identifying key concepts for casual observers.

The gallery also contained over 500 miniature buildings inspired by panelka—classic Soviet-era apartment blocks. Visitors to the gallery could contribute to the exhibit by gluing them in wall frames or in designated areas on the floor to create model cities. Inspired by the interactive bulletin boards he previously created as a Community Advisor, Mozhaev designed the buildings using a 3-D printer.

“The buildings provide a way to engage in the exhibition in a very playful and personal way,” said Mozhaev.

Scattered amidst the artistic works and academic papers were thought-provoking statements and questions related to the works at hand, such as “The past subsists as a ruin, only to be reinhabited once the political situation calls for it” and “Which is easier to remember—the distant labour camps where millions died, or the flavour of your favourite ice cream?”

Although Mozhaev hoped to foster a greater understanding of Russian reality through yebenya aesthetics and encouraged viewers to engage thoughtfully with the material, he also acknowledged that these concepts are too nuanced to fully dissect in a single gallery. In fact, he purposefully filled the gallery with an excessive abundance of materials to immerse the audience in the situation’s overwhelming complexity.

“It really takes more than a single visit—more than an hour, more than a day, more than a week—to digest all of this,” said Mozhaev. “It took me more than one term to bring together all of these different elements, and that’s what I want to convey. I’m not willing to simplify the complexity that I’ve come to notice while putting this together.”