There is not much that can be done or undone for the losses we accumulate in our lives. Little ones, big ones; they all count. We might lose our room keys on the way to the door or leave our wallets on the bus and only realize too late. Or we might lose our faith in the midst of disaster or lose our love in the wake of heartache.

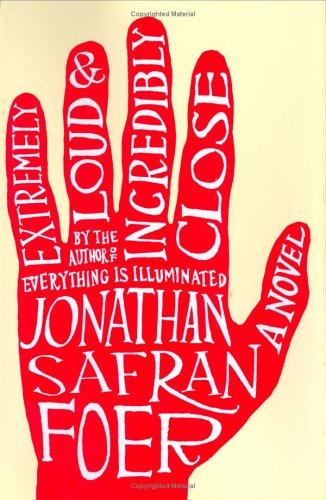

What sucks is that loss is inevitable and it will leave you winded, broken and bruised. The only consolation, of course, is that you are not alone. We have all been there — Jonathan Safran Foer included, whose novel “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close” will remind you of just that.

Exploring the nature of loss, grief and the complications of a life after tragedy, “Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close” brings forth a beautifully written and brutally honest perspective of loss and acceptance from the aftermath of the 9/11 tragedy. Foer wins his audiences over immediately, myself included, with his young and heart-breaking narrator.

Meet nine-year-old Oskar Schell: inventor, jewelry designer, jewelry fabricator, amateur entomologist, Francophile, vegan, origamist, pacifist, percussionist, amateur astronomer, computer consultant, amateur archaeologist and collector. Though brilliant and smart, Oskar wears heavy boots, his form of sadness and loneliness.

Oskar’s father, Thomas Schell, died in the horrific 9/11 attacks. While looking through his dad’s cupboard for anything tangible, anything to hold onto the memories, he accidently knocks over a blue vase on the top shelf. Upon smashing the vase, Oskar finds an envelope labeled ‘Black’ with a single key inside. From there, Oskar’s desperate but necessary journey in search of what the key might open begins. In an attempt to bring him closer to his father and to the answers of why he never said goodbye, Oskar introduces us to people from all walks of life including a 48-year-old divorcée and an old war correspondent who never turned on his hearing aids.

To some, the lack of the traditional linear style that is the norm for most novels may seem confusing or even annoying but push through and you will find that this book will make you laugh out loud and cry in silence. The novel, too, may feel extremely personal, invasive and too close to home. That is, however, exactly the point.

Foer may be ambitious in his attempt to help people deal with the grief and the trauma of tragedy by writing about it through the eyes of a child, but he deals with the themes of loss and loneliness so effortlessly that every word, fragment, page and photograph is where it should be. Foer depicts very well the battle between self-destruction and self-preservation within each and every one of us when faced with loss.

Do we choose to scream, cry, threaten suicide or murder, grab at our hair and punch a hole in a wall? We can. But after that, we can rub our knuckles, shake ourselves out and move on.