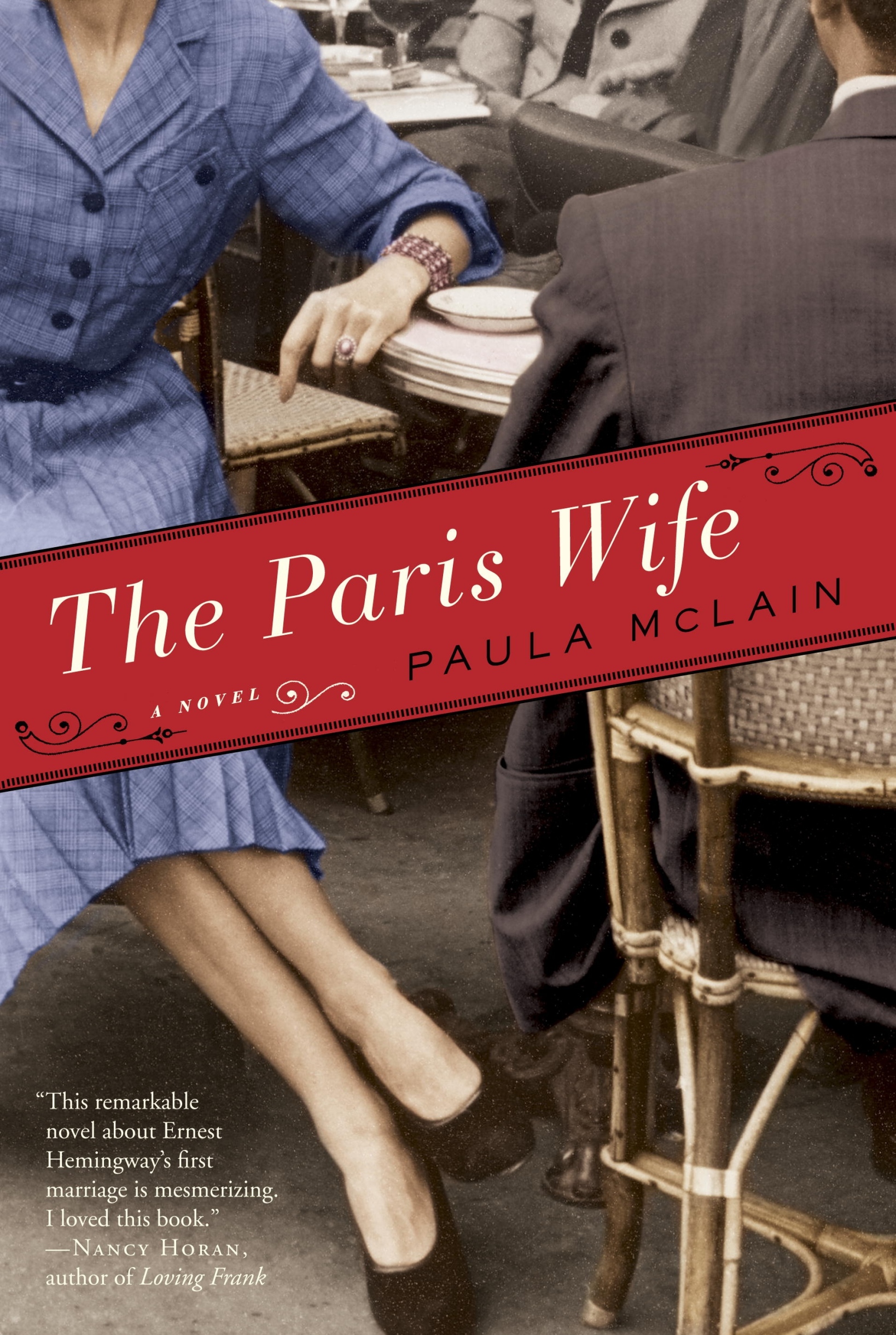

(Photo courtesy of Random House)

My experience with Ernest Hemingway is woefully limited; I’ve read a few short stories and that’s about it. I’ve liked what I’ve read, but he remains one of those authors I plan to get to “someday,” which could mean anywhere from this summer to 20 years from now. So when I picked up Paula McLain’s “The Paris Wife,” a fictionalized account of Hemingway’s early years narrated by his first wife, Hadley, I wasn’t sure if it would really speak to me. I knew that for me, the casual Hemingway fan, the book’s success would hinge on McLain’s ability to tell a story outside of Hemingway’s work.

I needn’t have worried. From the beginning McLain makes it very clear that while a large portion of the book will deal with Ernest and Hadley’s relationship, readers will also get a very different perspective than that found in Hemingway’s own memoir of this time in his life, “A Moveable Feast.” While I’m sure the story has an extra dimension for Hemingway aficionados, I enjoyed it immeasurably with just the little knowledge I have.

This isn’t the tale of a famous Hemingway at the top of his game, regarded as one of the premier writers of his generation. Rather, this is the story of a young Hemingway just trying to get off the ground, a Hemingway who takes his new wife to Paris because he has heard that is where all the writers write.

Much of the story concerns Ernest’s writing, but it is largely a tale of a young couple struggling to make it. Through Hadley’s eyes McLain introduces her readers to such greats as Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, and F. Scott Fitzgerald — all from the perspective of a “writer’s wife.” As much as the story is Hadley’s, it’s fascinating to see Hemingway from the perspective of a woman who loves him and to see how she copes with his moods and solitary tendencies.

We see Ernest as he develops one of his most famous characters, Nick Adams, and as he slaves over one of his most famous books, “The Sun Also Rises.” We even live some of the events that eventually became his plotlines. Ernest’s personality is large and magnetic, but McLain doesn’t let him take over the book; the main character and focus is undoubtedly Hadley. The novel begins with her life before she even meets Ernest and it doesn’t end with their divorce.

A common pitfall of historical fiction is authors trying to tell a story where there is none, and I hoped McLain would manage to avoid it. Again, my concerns were brushed away by the power of McLain’s story. Quite apart from being the story of a man, a woman or a marriage, “The Paris Wife” is a lovely portrait of the Jazz age and its main players, and McLain truly encompasses the carefree attitude of the time with her words. You don’t have to like Hemingway to enjoy “The Paris Wife” — all it takes is love for a good story.