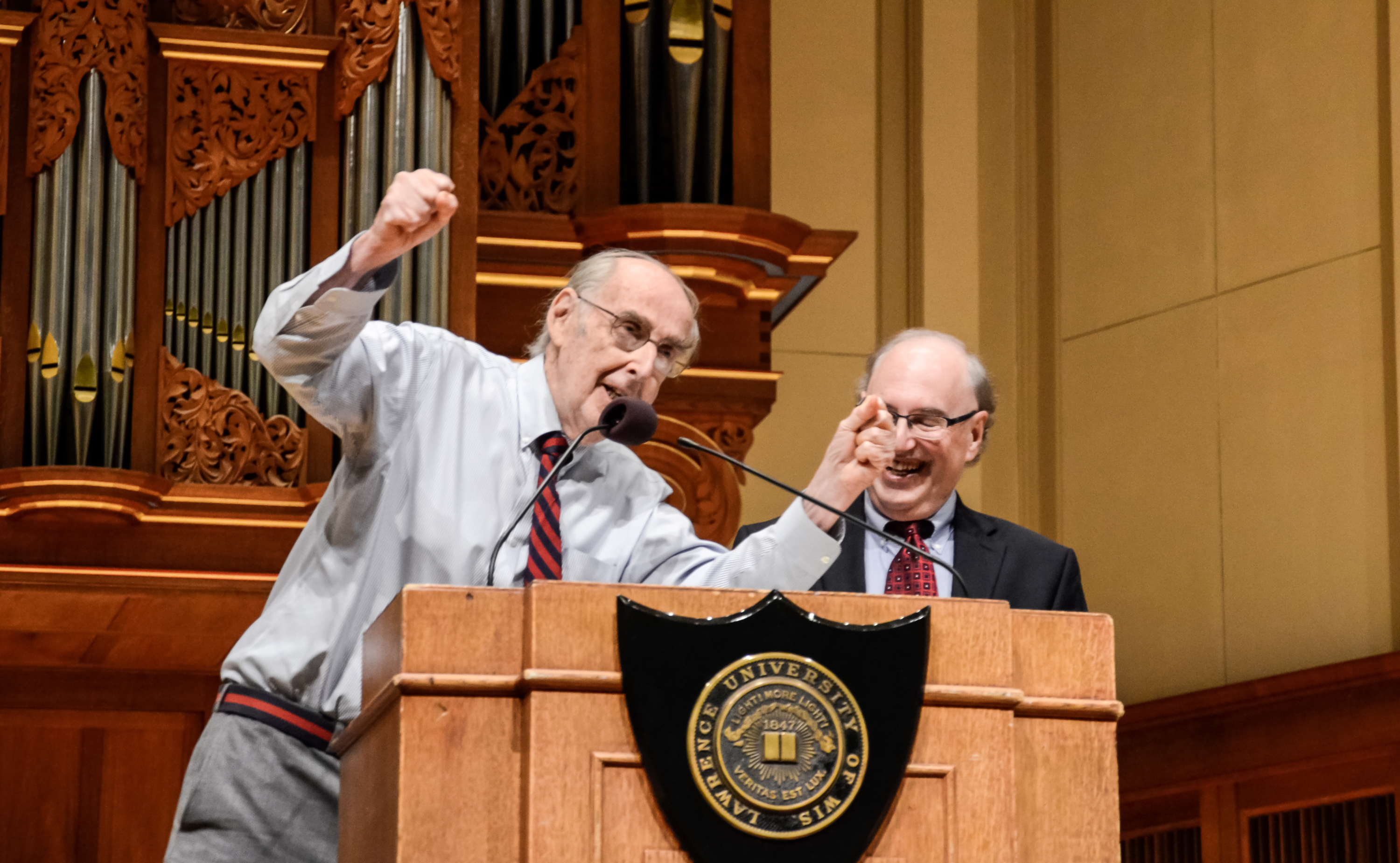

Colman McCarthy leans over the podium in front of Professor of History and Robert S. French Professor of American Studies Jerald Podair to chant “no more homework.”

Photos by Marieke de Koker

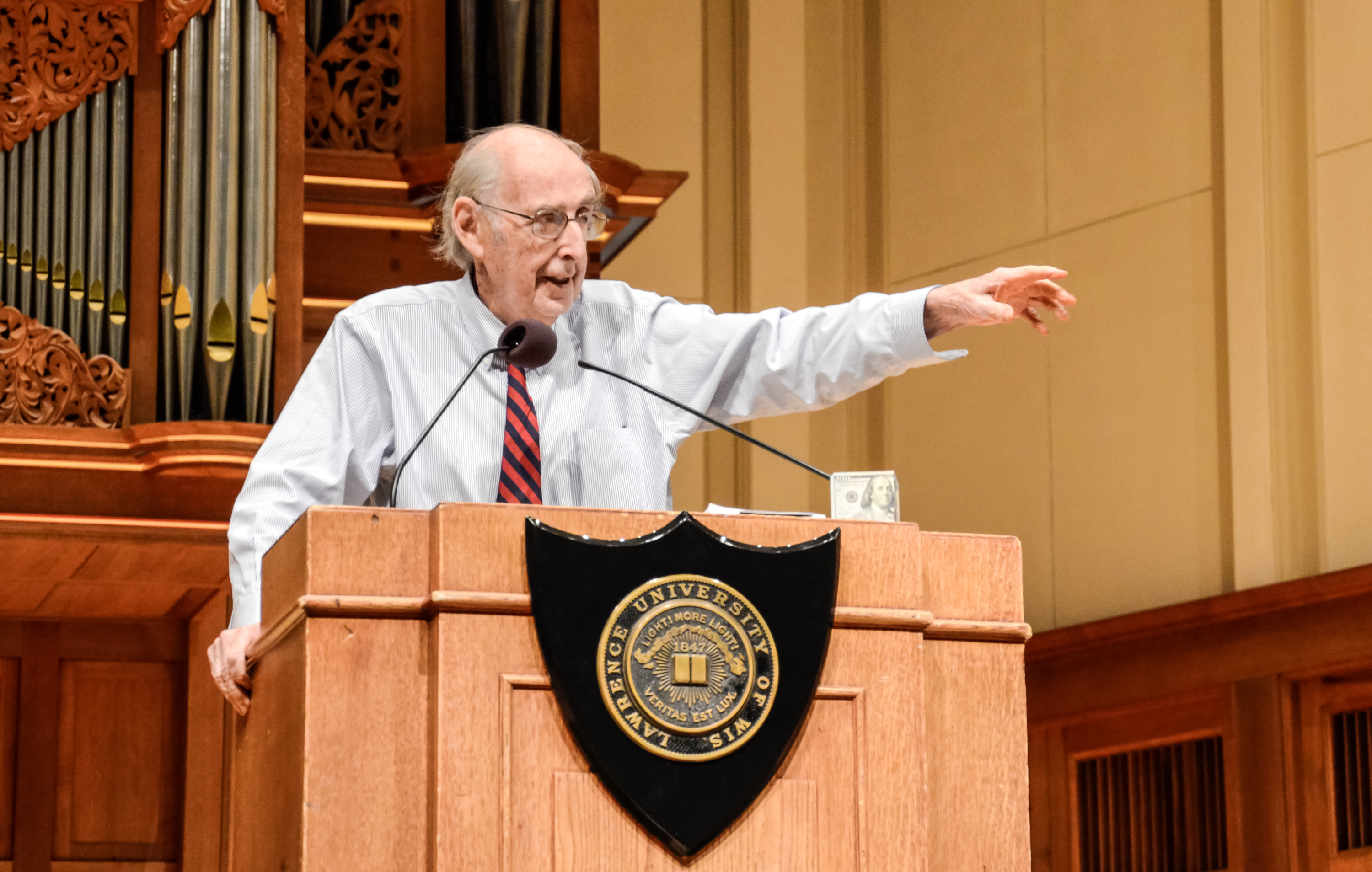

Posing the question “Is Peace Possible?” the esteemed journalist and activist Colman McCarthy was the guest speaker at Lawrence’s convocation on Tuesday, Oct. 31 to talk about his nonprofit organization Center for Teaching Peace and his experiences as a “peace-warrior.” After a brief Q&A, a lunch was held in Warch’s Pusey Room with a small group of students. There, McCarthy led a discussion mainly focusing on sexual violence at college campuses, as well as other topics such as patriotism, militarism and the value of international institutions such as the UN.

Professor of History and Robert S. French Professor of American Studies Jerald Podair introduced McCarthy at the convocation. He noted that McCarthy’s beginnings as an educator of peace can be traced back to his time at The Washington Post. One day after work, McCarthy marched to the nearest high school in the area and offered his services as a teacher for peace. The school was interested, but admitted that they had no money to pay him. As the story goes, McCarthy assured them that he didn’t care about the money, and so his first class began. At 79 years of age, McCarthy has reportedly taught the concepts of peace to around 7,000 students in over 25 years.

Podair went on to describe the structure of McCarthy’s classes, which feature no exams, no grades and no homework. At that, Mr. McCarthy stood up and walked over to the chapel podium, whereupon he seized the microphone and started chanting, “No more homework! No more homework!” It was one of the convocation’s many highlights.

Throughout his thirty years as a journalist, McCarthy interviewed many of the great pacifists of the twentieth century, including Mother Teresa, Janette Rankin and R. Sargent Shriver. He spoke of the friendships he developed with them, and the way that they influenced him as an advocate for peace.

As a young freelance writer, he interviewed Martin Luther King Jr. before a march in Cicero, Illinois in 1966. Afterwards, he developed a correspondence with King, gaining some insight into the visionary’s more “radical” views. For example, Martin Luther King Jr. was adamantly against the war in Vietnam, and once called the United States’ government “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.” McCarthy believes that sanitizing King and others reflects major deficiencies in the American education system. On the other hand, he firmly considers education, or “pure learning,” to be the vehicle by which peace can be made a reality.

It was with this conviction that he founded the Center for Teaching Peace in 1985, a nonprofit that “helps schools begin or expand academic programs in Peace studies.” In these classes, students read texts by McCarthy himself and by classic writers such as Hemingway, Tolstoy and many others. He is also a regular speaker at high schools, college campuses, prep schools and conferences all around the country. From McCarthy’s perspective, peace is created at the individual level when each person decides to “be different” and “break away from our culture of violence.”

For McCarthy, violence can take many shapes and forms, and some are made more visible than others. He differentiated between “hot violence,” like Las Vegas massacre earlier this fall and “cold violence” like domestic violence, imperialism and even the exploitation of animals in the food industry. McCarthy sees all violence as corrosive and daunting. However, he stressed that while peace is not necessarily “probable” it is unquestionably “possible.”

“On the first day of class,” said McCarthy, “I always tell my students the same thing: Don’t ask me any questions. Instead of asking questions, question the answers.”