(Madhuri Vijay)

Madhuri Vijay ’09 was one of 40 national recipients of a $28,000 fellowship from the Thomas J. Watson Foundation. The grant supports a year of independent study and travel outside the United States to research a topic of the student’s choosing. Vijay, who hails from Bangalore, India, is currently using her fellowship to visit different parts of the world and explore the lives of Indians like herself who have left their motherland behind. This is the first of a four-part series that will document her travels.

The daladala that my aunt, who has come to visit, and I have taken from our hotel to Zanzibar’s Stone Town stops in the middle of the bustling local vegetable market to unload its passengers. The daladala is basically a long, low auto rickshaw, crammed full with passengers, and we have just spent the better part of an hour in it. We clamber out, sweating and already tired, and we look around uncertainly, obviously quite lost, until a young man holding a briefcase – he looks like a student – kindly points us in the direction of the tourist market. As opposed to the local market. Thereby quite clearly drawing the line between us and them.

We begin walking in the direction he has pointed out, but we are soon swallowed into Stone Town’s narrow, winding streets. The buildings all look the same to us, flat-fronted, with balconies from which flutter laundry and the leaves of potted plants. We pretend like we know where we’re going, but at the first opportunity, I stop and ask a pair of Indian storekeepers the way to the tourist market. I speak in Hindi, knowing that it is close enough to the locally spoken Gujarati to perhaps forge a bond with them, and it works. They look slowly at each other, and the younger one rises, with the help of crutches. I notice right away that his left leg has been amputated at the thigh.

“I’m going that way myself,” he says. “I’d be happy to show you the way.”

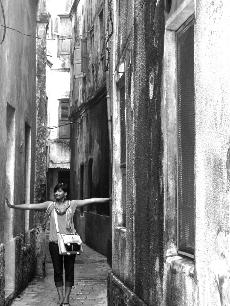

Thus begins one of the strangest, most impromptu city tours I have ever received. Our new self-appointed guide, let’s call him Ali, moves unerringly through the narrow streets, under arches, past elaborately carved Arab doors. Despite his crutches and missing leg, he manages to keep up with us. I wonder what happened to his leg, but I don’t have the courage to ask.

He talks about Stone Town as we walk, about its history as the center of the slave trade. He shows us the sea front, the orphanage and the fancy new hotel, all developed by the Aga Khan. He takes us to curio shops and waits outside while we linger inside, greedy for the air conditioning. He talks about the Revolution of ’64, and the relationship between the Indians and Africans in Zanzibar. He is a history, geography, anthropology and cultural psychology lecture rolled into one.

But, as he is telling us all this, he also tells us about himself. Or rather, his own story also emerges beside the story of his hometown, whether or not he intends for it to be so. He shows us the house in which he was born and spent most of his childhood. He takes us to the Africa Hotel for Cokes, and laughs when we remark that all the hotel’s staff members seem to know him. He says he doesn’t drink alcohol and adds, with heavy distaste, that many of Zanzibar’s Muslims aren’t Muslim in practice any longer, but he still sticks to his principles. Sitting on the balcony of the hotel, he points down to the broad boulevard that runs beside the ocean and says he used to come there to play as a child. When my aunt, who, as a doctor, is far more frank about medical matters than I am, asks what happened to his leg, he speaks of an accident as a child, a wound he received while playing and hid from his parents for many years, fearing their anger, until he could hide it no longer. But by then, of course, it was too late to do anything about it. He went to India for the operation, and when he hears that my aunt is a doctor, he says, “We need good doctors here in Zanzibar. We don’t have enough.” He speaks of his marriage and its failure, the two children that his mother is now bringing up. My aunt and I look at each other, and I bite my lip, but neither of us asks what happened to his wife, or where she is now.

In this way, we learn about Ali and about Stone Town at the same time, the personal story coming to light at the same time as communal history. Time slithers through our hands, and before we know it, we must leave. He haggles with the taxi driver in order to get us a reasonable price back to our hotel, and tells me firmly to call him if we have any problem whatsoever on the way back. He stands waving as our taxi drives away. We don’t return to Stone Town during that trip, and I will, in all probability, never see him again. But my memories of those narrow streets are colored by his presence in them, and his movement through them, and though we didn’t see what most of what tourists usually come to Stone Town to see – the museum, the surrounding islands, the Spice Tour – I feel like I understand something essential about it, though I could not name clearly for you what that something is.

(Madhuri Vijay)