“If NASA wants to put five people in an enclosed box for six months and ship them off to another planet, it’s going to have to be somebody’s job to design the inside of that box.”

Senior Charles Brailovsky is currently on a leave of absence, delaying his psychology capstone in favor of a coveted internship at NASA in Huntsville, Alabama. While the Marshall Space Flight Center where he reports for work is just one small step from the site of NASA’s well-known Space Camp, Brailovsky has taken a giant leap from the six-day space education program as he gains experience in what he describes as his dream job with a human factors engineering team whose task it is to design the interior aspects of spacecraft for maximum ergonomics and intuitive use.

Also known as engineering psychology, Brailovsky describes human factors engineering as a field concerned with “designing things around the needs of humans” that asks the question: “how can you make a system functional in such a way that it limits the chance of mistakes?” To highlight the critical nature of the discipline, he recounts one of NASA’s most devastating space travel accidents – the Apollo 1 cabin fire in 1967.

In preparation for the US’s first crewed moon mission, three astronauts boarded the Apollo 1 for a simulation of the launch planned for a month later. After the crew was sealed inside and the cabin pressurized, an electrical fire broke out and spread rapidly in the pure oxygen atmosphere of the vessel. Both the astronauts and the ground crew struggled to open a set of three hatches in oppressive heat and with smoke obstructing their sight.

Due to the high air pressure inside, the on-board crew never managed to open the inner hatch, which opened inward. By the time the ground crew wrestled open the outer and inner hatches, all three astronauts had perished from the fumes, the mission ending in tragedy before it even started.

Following the disaster, NASA’s investigations revealed several factors that led to the fire and failed evacuation. One of the design revisions for subsequent Apollo missions was a revised hatch that could be opened from either side in three seconds, as opposed to the 90 seconds it would have taken the Apollo 1 crew. Design decisions such as hatch mechanics are the priority of Brailovsky’s team over fifty years later.

Explaining a project from before he joined the team, Brailovsky describes how his colleagues conducted experiments that combined perfunctory physical models with detailed virtual reality displays. Subjects in VR headsets and motion capture suits interacted with potential hatchway designs so the team could later perform a human factors analysis to determine how to re-engineer the hatchway for more efficient use, considering aspects like the shape, size and corners of the opening.

Brailovsky admits that most of his first week on the job was spent helping his new team move between buildings or doing administrative and on-boarding activities, but even so, merely being at the facility fills him with wonder. “It’s been totally amazing to just be here with all the space stuff,” he says. “I mean, I drive past a Saturn V rocket every morning to get to work!” Even inside the building, his desk space sits under a suspended, 4-story prototype for a long-term space travel habitat.

Of course, he has plans to make himself useful outside of moving offices, having just submitted his long-term project proposal for holographic desktop interfaces on spacecraft. Brailovsky plans to develop a proof-of-concept prototype for stationary hologram monitors that astronauts can see through virtual reality headsets like the Microsoft HoloLens but will not take up any actual space in hopes of cutting down the weight of future spacecraft.

Brailovsky shares that his time at NASA so far has not been completely idyllic; he has ADHD and must manage the onset of brain fog by the time the afternoon hits each day, but the general awe he described previously offsets a lot of the other challenges. “Where I work, Redstone Arsenal, is where NASA began,” he explains. “This is where they launched the first satellite. This is where they designed, tested, and built the first Saturn V.” That, combined with the chance to immerse himself in learning at the edge of his ability and the frontier of his interest, has given him “a chance to weaponize hyper-fixation.”

It has not always been smooth sailing when it comes to his ADHD, though – Brailovsky considers himself lucky to have even gotten into college considering the state of his grades before he began treatment. “This has been my goal since I was 15, to work at NASA in human factors,” he says, but after failing some classes during COVID and having to drop his second major in computer science, “it seemed like NASA was just not going to be an option anymore.”

Just as he was planning to pivot into neuropsychology and ADHD research for his capstone, giving up on space exploration for the time being, Brailovsky tried applying to one final internship at NASA’s Johnson Center. The position combined his interest in space travel, engineering and cognitive psychology with his previous passion and experience in computer science. The Johnson Center team was looking for applicants who could code in C# and work in the Unity game engine for augmented reality, and Brailovsky had just finished an internship at Iowa State University where he had focused on virtual reality programming.

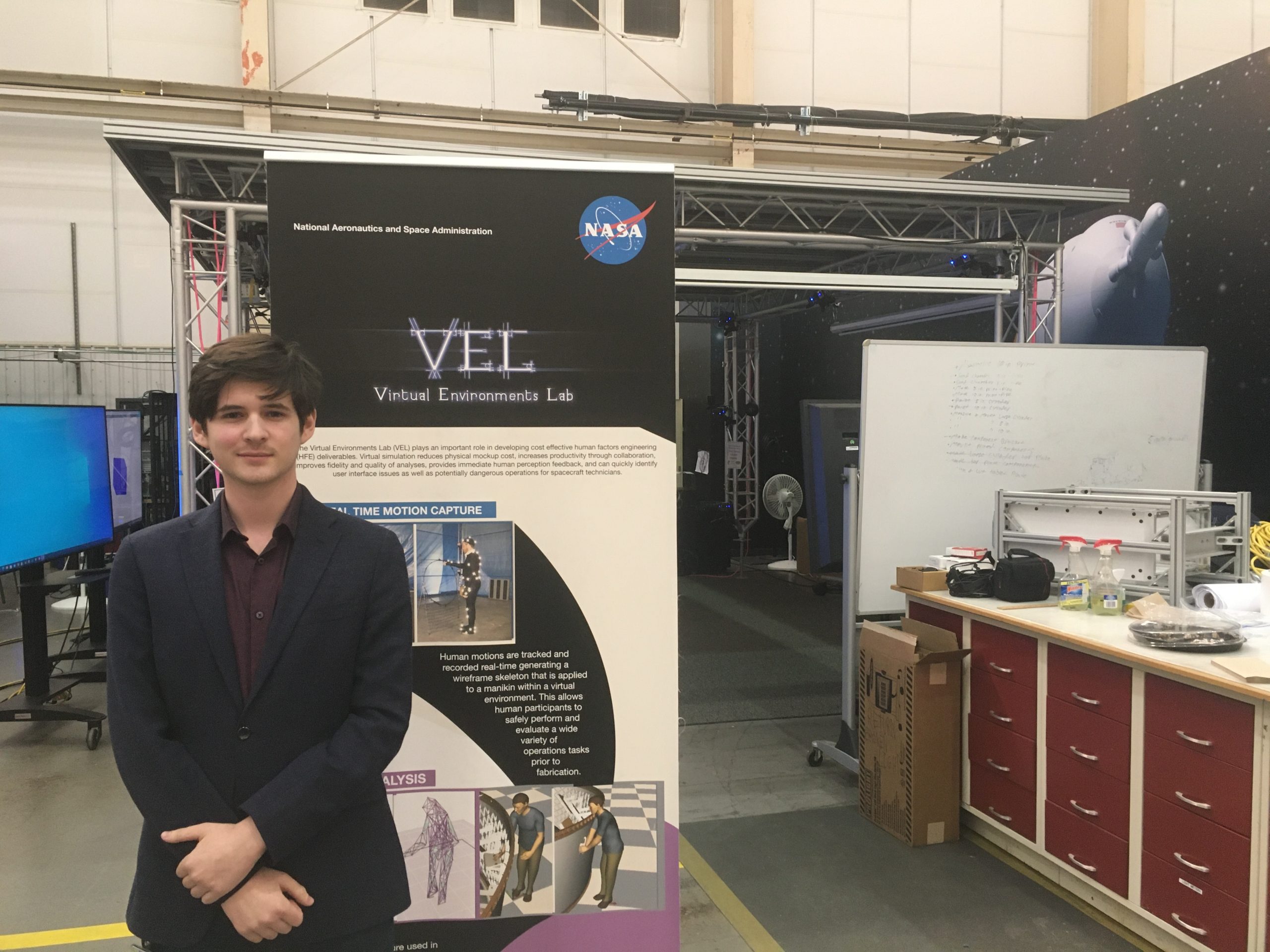

It was a perfect fit for Brailovsky’s aspirations, but he did not get in – and that did not surprise him, at a time when he felt like he was going nowhere. At the same time, though, his current mentor at the Marshall Space Flight Center was looking for someone with the same combination of experiences and reached out to him to apply for her Virtual Environments Lab instead, where he is now the sole intern. Though he admits that some credit is due to him for the work he has put in, Brailovsky concludes that “there’s no two ways about it – I’m very lucky.”

In retrospect, Brailovsky has been on his current trajectory since childhood – he had an early obsession with PBS space documentaries narrated by Neil DeGrasse Tyson and Carl Sagan and was “playing around” with code by age 10, later teaching himself the basics of Python. Even when his dream job seemed to slip out of reach, Brailovsky still had a plan in the back of his mind – “but it was a long-term plan,” he qualifies. “I was building the skills and I thought I would have to keep building them for at least another four or five years.”

He once again credits pure luck for his early chance at his ideal internship but has some advice to give when pressed for it: “Find out what kind of industry you want to work in and talk to people who already work in those fields.” He recommends simply reaching out to professionals and academics online – many are happy to talk. “You don’t even need to know what kind of job you actually want, just a vague idea,” he assures. “Find out as early as you can what kind of skills are used in those fields and take every chance you can to get those on your resume.”

As the only candidate in his pool with the exact combination of required skills, that strategy certainly worked out for him. Now, Brailovsky has months ahead of him of “some of the coolest stuff [he] could possibly be doing,” not to mention a lot more self-assurance in his own skills.