(Lawrence University)

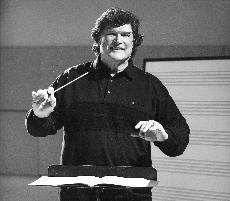

Professor David Becker, music director of the Lawrence Symphony Orchestra, began his teaching career here in the mid-1970s. Life took him elsewhere for a time, but he returned in 2005, and at the 2010 commencement was presented with Lawrence’s “Excellence in Teaching” award. The Lawrentian sat down with Professor Becker in hopes of learning about the ups and downs of a life in music.

Introduced to music at an early age by his father, who was a bluegrass player, Becker started out on the violin. But because of his height – in ninth grade, he stood 6 feet 6 inches tall – he was encouraged to switch to the viola. Perhaps because of his imposing stature, Becker was also in demand as an athlete. “Being [both] a jock and a musician was a part of my life,” he said.

Becker studied music education as an undergraduate, inspired in large part by the conductor of his high school orchestra. It was clear, however, that performance would figure prominently in Becker’s path, and right out of school, he began a rich and varied career in the world of classical music. Rubin: Tell me about your early career as a performer.

Becker: I left undergraduate school and noticed that there was a job opening for the Louisville Symphony. I got the audition, and while I was there, they encouraged me to get my master’s degree at the University of Louisville, while I was playing professionally. And then from there, someone invited me to come audition for the Atlanta Symphony. I did that, and my life started going from there.

Rubin: What was your experience like in Atlanta?

Becker: I was a young kid in the Atlanta Symphony. I wasn’t disciplined, didn’t know the routine, and didn’t know the repertoire. I was practicing all day long, just to keep my head above water. Learning what it’s like to be a professional orchestral preformer [was] very challenging, but I loved every moment of it.

At that time, the conductor was Robert Shaw, who was a great choral conductor. [He] influenced me so much, musically, spiritually and intellectually. Luckily, every season, Shaw hired a musical assistant. The job was: to go to [Shaw’s] house and get his bowings and markings, and take them to the librarian of the Atlanta Symphony. When he finished a score, which could be anytime – at 2 a.m. – he would call and say “David, come over and pick up my score.” He would sit down and go through the Ives fourth symphony – for example – and say “Here’s why I’m doing up-bow,” or, “Do you think we should do this slur?” It became a conducting lesson. I saw his incredible dedication and commitment, 24 hours a day, to his art form.

Sometimes things that seem like menial jobs – pick up the score and take it to the librarian – turn into a more profound situation that influences your life. Whatever comes your way, take advantage of it. I really believe that.

Rubin: When did you decide to go into conducting and teaching, and how did that unfold?

Becker: I think I had already decided as an undergraduate. I was blessed to go to an outstanding school to student teach, in a small town in northern New York called Wellsville. [It] was one of the most outstanding high school orchestras – to this day – that I’ve heard in my entire life. It was all run by one person. That’s when I was convinced: “I’d really like to do this.”

My first official teaching position was at Lawrence University. They approached me and said: “Would you be interested in leaving the professional performing world in order to come and teach here?” [It was] an invaluable experience that totally changed my life. Then I was called by Oberlin, then Memphis State University, University of Georgia, University of Miami, University of Wisconsin-Madison and so on.

Rubin: Now that we’ve talked about your background, I’d like to ask about life nowadays. Do you like to do anything on the side, outside of music?

Becker: I think that being a performer – or conductor – does absorb a lot of your time. If you enjoy doing that, then it is your hobby. I’m also blessed with two things. [First,] a wonderful wife who enjoys hiking and traveling. We’re on the road all the time. Unfortunately, we have a long-distance relationship. My wife teaches in Madison, so I have to get back and forth whenever I can. I’m also blessed to have three sons, and one of my sons is a professional rock musician. He plays in a group called “Cherry Pie,” which is based in Milwaukee. Whenever he does a solo gig or a band gig, if it’s within driving distance, I go. My arrangement with my sons, from when they were little kids, was: for every concert [of mine] that they would come to, I would go to one of their choice. It has been great for me, to get my head out of Beethoven scores.

Rubin: Many of our readers in the college might not realize the many different roles of a conservatory professor. Can you tell me about the challenges and rewards of conducting an orchestra, for instance?

Becker: There is a distinct difference between having a professional orchestra and having an academic orchestra. I would like to believe that the artistic integrity is the same, but the educational function is totally different. A prime example is this year with the LSO. We just graduated 39 seniors. We have just entered a rebuilding period… and I think it’s terribly exciting. Is it challenging? Yup, absolutely. It would be like starting a football team with 39 players not coming back. Setting the standard is important, but being realistic and nurturing, I think that’s important [too]. You do have to be nurtured into the routine [of conservatory study].

There are outstanding students coming into Lawrence, there is outstanding leadership by our upperclassmen, and then there is the distinguished applied faculty… you put it all together, and you’ll have a respectable ensemble. That’s more important than the conductor, in my opinion.

Rubin: On a lighter note, are there any musicians who you look up to as mentors? Do you listen to recordings, for instance?

Becker: I spent the majority of my life playing in orchestra and watching guest conductors come by. [I had] a chance, you know, to see Copland and Stravinsky on the podium. [That said,] I am also interested in historical recordings. I’m interested in Weingartner, Fürtwangler, von Karajan. What was their approach, given the performance practices of their time? We now live in 2010. How much [should] we follow tradition?

I try not to listen to a lot of the music that I’m performing, because I’d like to study the score and see if I can find the piece on my own, without being influenced by somebody else’s tempi. I tend to listen to music that I’m not performing at the time. [Often], that – i.e. interpretation – is finalized once you start making music with musicians. Those people sitting in the room in LSO are determining the interpretation. That’s hard for students to understand. Together we make music. We do it together. There is no demagogue on the podium.

Rubin: Do you feel a particular affinity with any composers?

Becker: This is very trite, and it’s said so often, but my favorite is the one I’m [conducting] at the time. I throw my life into whatever we’re doing at that moment. If I have only an hour left, and I’m going to leave this space and go somewhere else, then probably it would be: Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Mahler, Strauss, Bartók, Messiaen, etc. As a performer, we have to believe in the piece we’re playing right now. All of a sudden, that composer becomes the most important person in your life. You enjoy where you are at that time.

(Lawrence University)