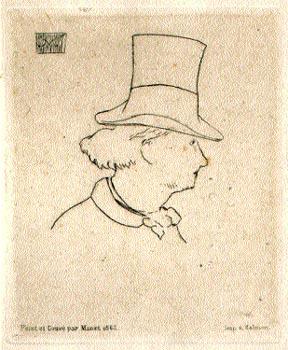

Mamet&s &Man in Top Hat& illustrates Bandeliere, both a poet and a modernist.

On Nov. 16, Wriston Art Center opens Modernity and the Fragment, an extensive exhibition of modern art from Wriston’s permanent collection. The works encompass the idea that the modern world is a fidgety thing that refuses to sit for its portrait and constantly changes its attitudes. This idea is especially relevant in the context of America’s present struggles. Once we believe we understand the anti-terrorist strikes or the impending economic slide or the threat of biological warfare, the volatile, dynamic system changes, and we are once again ignorant of knowledge of the whole. Modern artists’ sentiments cover the idea that we can begin to rationalize this whole when we examine its fragments and become like archeologists glimpsing a past culture through the discovery of its artifacts.

Wriston Gallery curator Frank Lewis led me through this intriguing exhibit, describing motivations for modernity’s advent, and giving me a sneak preview of some highlights from the show.

In the early 1800s, Lewis explained, the speed and complexity of the world seemed to accelerate, prompted by industrialization and urbanization. Due to the factory system, people began to produce fragments of a whole and even to become fragments of the machines of production, said Lewis. In addition, he explained, to the social fragmentation of industrialization, archeologists began to unearth fragmented remains of past cultures. The changes and discoveries of the era, according to Lewis, caused the modern world to refuse pause for the onlooker to gain a cohesive knowledge of the whole.

This is why, explained Lewis, artists, especially impressionists and German expressionists, began to depict the world in the only way they thought accurate: in glimpses through fragmented parts of an inconceivable whole.

As Lewis browsed through large stacks of the exhibition’s prints, the simplistic “Man in a Top Hat” (1862) caught his attention. The sketch, by Manet, depicts the French Romantic poet Baudeliere. The poet Baudeliere reveled in modern life, and believed that the world had passed the point of no return in its progression or perpetual motion. The world, in his perspective, could never be returned to its past simpler state, especially since the innovation of streetlamps could turn night to day and erase the significance of time itself.

Manet’s sketch is not much more than a profile, but Manet argued that the viewer could never know Baudeliere and his contributions to modernity from a print, but only recognize him and begin interpreting this fragment of a complete organism.

Modernity was also influenced by Freud’s idea that dreams are not cohesive, but demonstrate the surrealism of a fragmented life.

Included in the upcoming exhibition is a work by Renee Margritte titled “Les Bijoux Indiscrets.” Among the stacks of prints, Lewis revealed the surrealist charm of this work: a disembodied “close-up” of a slender hand with a dreaming face nestled into its wrist. The idea of the close-up was also a modernist concept, since the subject is a fragment of a larger being. This curious object rests against an ambiguous background; the viewer should wonder if the hand rests on a tabletop or if it is the featured foreground in a much larger landscape.

Lewis next described a piece by J.M.W. Turner, an early modernist. While other modernists downplayed the importance of nature with society flocking to the city, Turner believed that nature was too immense for human understanding. In an engraving, “Llanthony, Manmouthshire” (1836), Turner highlights the idea of archeological finds as fragments in the context of a vast natural background.

In this work, the ruins of an ancient church are backlit by the soft light of the sun, which symbolizes an eternal force in nature. In the foreground, a small cluster of people huddle, frightened, in the shadows, fragmented from the perceived glory of the sun by a tumultuous river in the center of the scene. Lewis pointed out that Turner’s work represents the beauty and brutality of nature while demonstrating that humans are separated from nature’s immensity through our inability to conceive of the whole.

An etching by John Marin, “Sailboat” (1932), is also included in Modernity and the Fragment. This intriguing sketch of a lithe but strong vessel demonstrates both viewers’ fragmented perception of movement and the inseparable energy of the boat, the sea, and the sky. Marin’s bold pencil strokes divide the ship into separate units of motion or perception. But, as Lewis pointed out, it is difficult to discern between the energetic lines that depict the clouds and waves and the lines that depict the ship. It is impossible to understand the whole complex scene, but it is also impossible to separate the energy of interacting fragments.

Modernity and the Fragment opens with an introductory lecture by Frank Lewis at 6:00 p.m. on Nov. 16th, followed by refreshments until 8:30 p.m. The exhibit runs until Dec. 16, and is free and open to Lawrence students and the public during normal gallery hours: 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. Monday through Thursday, and noon to 4:00 p.m. on Saturdays and Sundays.