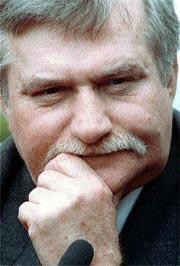

Lech Walesa, a man that Timothy Garton Ash, the Oxford historian and author of The Polish Revolution: Solidarity calls “the fly, feisty, mustachioed electrician from Gdansk,” has represented the fight for freedom to the entire world. Throughout the 1980s, he symbolized many ideals to people everywhere, including the struggle for human rights and the power of one individual to change the world. Those who attended his Thursday convocation or question and answer session saw history in the flesh, and heard from someone whose gift with words has had a huge impact on the fate of millions of people.Walesa’s story is one of humble beginnings that turn into something larger. The Solidarity movement that he was instrumental in creating in 1980 began as a workers’ demand for free trade unions. In almost no time after its founding, the movement came to represent not only a fight for human rights, but also a victory against the oppression of the Communist Eastern Bloc. These two values were recognized by the Nobel Committee, from whom he received the 1983 Nobel Peace Prize.

Personally, Walesa was born to a family of peasant farmers. He graduated from vocational school, worked as a car mechanic at a machine center, served in the army for two years, and in 1967 was hired in the Gdansk shipyards as an electrician. Partly because of his devout Catholic background, an influence that was to become very important later in the Solidarity movement, he was shocked by the repression of laborers, and helped lead the shipyard workers in a Dec. 1970 clash with the government. His activities during the 1970s towards organizing non-communist free trade unions led to his being fired, detained frequently, and constantly under surveillance during the last part of the decade.

In Aug. 1980, the Lenin shipyard workers at Gdansk went on strike, and Walesa famously climbed over the fence to rejoin his former co-workers. The success of the strike led to a wave of strikes throughout Poland. Within a month, as their leader, Walesa was able to negotiate with the Polish government on behalf of the workers the right to organize an independent union.

Just over a year later, the Polish government, fearing Soviet armed intervention, imposed martial law, and the Solidarity movement was banned. Walesa was targeted, and declined to accept the Nobel Peace Prize in person for fear of being kept out of Poland. However, as economic conditions in Poland worsened, the government was forced to reopen negotiations with Walesa and the Solidarity movement. By 1990, he was elected Poland’s first non-communist president.

Walesa’s influence has lasted beyond his presidency, which ended in 1995. While his popularity in Poland has waned in recent years, partly because of his personal style that was more suited to freedom fighting than to presidential politics, his legacy is inspiring to the individual who sees the need for change. As the Nobel Committee put it, his Peace Prize reflected “homage to the power of victory which abides in one person’s belief, in his vision and in his courage to follow his call.” His work is both personal and collective, nationalistic and universal.

Check out our website, www.lawrentian.com, at 6 p.m. on Friday for a complete report on Thursday’s Lech Walesa convo.