To curator of the Wriston Art Gallery Frank Lewis and his assistant Ester Fajzi-Degrot, art in the attic, or more appropriately, the boiler room, is a recurring theme in the ongoing inventory of Lawrence’s Private collection. Earlier last week, while searching a boiler room beneath one of the on-campus houses, Fajzi-Degrot came across a rather interesting find. Propped up against an old furnace, and framed under glass, was what appeared to be a very large poster. Upon further investigation, however, the piece turned out to be a large, and very detailed, etching. Comments Lewis: “The piece turned up unexpectedly in our inventory. We had no record of it, and it was a complete surprise.”

With little to go on but a nearly illegible signature scrawled in the lower right corner of the piece, Lewis and Fajzi-Degrot began their research to name the artist as well as to date and title the piece. And what they found was one of Great Britain’s best. Explains Lewis: “Ester, the student interns, and I decided the signature said ‘Frank B-r something, so we proceeded to go through the list of known artists and came across one or two possibilities. We then looked at the style of the print, the size, dated it to the 19th or 20th century, most likely 1916-1924, and realized the artist was Frank Brangwyn.” Interestingly, in delving into the archives of the private collection, Lewis realized that Lawrence was already in possession of one of Brangwyn’s smaller prints, as well as a book in the Mudd library on the artist.

Brangwyn was a much celebrated English artist who worked independently of the movements of the time—Impressionism and Art Neavou—in favor of pioneering his own style. Born in 1867 in Bruges, Belgium, and raised in London, Brangwyn had only five years of schooling before he dropped out to work in his father’s art studio. At the age of fifteen he was apprenticed to the established artist William Morris, and at the age of seventeen was accepted into the Royal Academy of Art.

While simultaneously enjoying the fame his talents earned him, Brangwyn spent much of his early career in utter poverty, and painted traditional seascapes using only shades of grey, the limits of his pallete reflecting the limits of his funds. His Funeral at Sea (1890), however, won him a gold medal at the Paris Salon of 1891, and some international acclaim. In 1888, Brangwyn indentured himself on a freighter in exchange for passage to the Near East to explore the fascination with Orientalism that was a driving force in European art at the time. Brangwyn returned home with a new perspective, and began turning out the bright hues and fantastical scenes he became famous for.

A self-taught painter, Brangwyn explored a variety of different mediums as well. He became well-known in the United States for his book illustrations which were featured in magazines like McClures and The Century, and greatly influenced American Art Neavou. He painted murals in public areas for cities from San Francisco to London, and experimented with watercolor.

Brangwyn also sought to revive etching as a medium and art form, which had fallen out of vogue by the early 20th century. Etching is a medium which involves coating a metal sheet with acid-resistant varnish, then carving a design through the varnish with a needle that exposes the metal. The sheet is then coated with acid, thus imprinting it with the design. After the etching is covered with ink, excess ink is wiped away, and a piece of paper is pressed over the design, a process which allows for numerous reproductions.

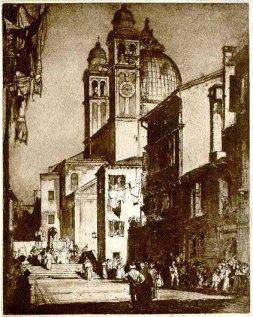

Inspired by early pioneering artists like Goya and Rembrandt, Brangwyn employed a variety of their techniques in his etchings, while developing some of his own. In the as-of-yet untitled piece just discovered, which depicts a bridge amidst a series of buildings, many of Brangwyn’s “experimental” techniques are present. As Lewis explains: “The piece is a classical model of a landscape and a wonderful art historical piece. Brangwyn combined the selective removal of ink to create a background that glows with tone, and used resin, which adheres to the plate without melting, as well.” Brangwyn also alternated his use of deep cuts and light scratches in his plates to create contrast in his piece, and was constantly altering and revising his work.“

Brangwyn had a romantic view of Europe and was really interested in an expressive manner and meaning,” Adds Lewis, further stating, “He revived the view pictures that were popularly collected as souvenirs during the grand tours the wealthy took of Southern Europe, and was interested in commercial marketing, in the public, and his own success.”