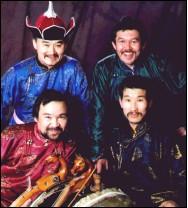

Huun-Huur-Tu performed two sets at the Old Town School of Folk Music Saturday (courtesy of Huun-Huur-Tu)

The art of throatsinging is becoming a distinctive force in our culture, with artists like Bjrk and the Kronos Quartet featuring throatsingers in their music. Yet few of us actually have the opportunity

to experience this phenomenal craft firsthand.

One such opportunity arose last week when the Tuvan quartet Huun-Huur-Tu performed at the Old Town School of Folk Music in Chicago.

If you’ve never heard Tuvan throatsinging,

it’s hard to describe. Called “khmei”

in Tuvan, it’s both beautiful and abrasive, both sonorous and guttural. Some people compare it to the sound of an Australian didgeridoo, but it’s a little more complex and varied than that. Basically, khmei involves the singer constricting parts of the throat and shaping

the tongue so that a high second pitch emerges. By moving the tongue, the performer

can sing a melody while holding the base note.

Huun-Huur-Tu, whose members hail from Kyzyl, the capital of the Siberian republic of Tuva in the Russian Federation, is currently on their 16th U.S. tour, having mostly stuck to performing since 2004’s “Altai Sayan Tandy-Uula” with then-new member Andrey Mongush.

The members all sang both in various

styles of throatsinging and in more conventional voices. They also each played two or three instruments. Kaigal-ool Khovalyg, a co-founder of the group, did a majority of the overtone singing and played mostly on the “igil,” a bowed instrument similar to the Chinese erhu. Sayan Bapa, another original member, sang in the deep, resonant “kargyraa” style and mostly played doshpuluur, a three-stringed lute. Alexei Saryglar contributed

a great deal of melodic singing and played various percussion instruments

which included a “tungur” shaman drum, horse hooves, and several others. Mongush was featured both as a throatsinger

and for his strong, lyrical “normal” voice, as well as playing flute and several stringed instruments.

Huun-Huur-Tu played two shows Saturday night, selling out their 7 p.m. performance and nearly doing the same at 10 p.m. The setting was lively but intimate in the 357-seat American Airlines Concert Hall at Old Town’s Lincoln Avenue location.

The quartet played for just over an hour, with Bapa briefly introducing each song.

The concert featured two exceptional solos that allowed the audience to hear the throatsinging separated from the instruments. Mongush sang in the “sygyt” – or “whistle” – style, a technique that produces a very clear, loud, overtone. Later, Kaigal-ool Khovalyg sang in “mountain

kargyraa,” for which the singer must vibrate not only the vocal folds but also the usually unused ventricular folds. This produces a fundamental an octave below the sung pitch in addition to the high overtone.

One particularly sublime song was “dugen Taiga,” about the sacred ground at the confluence of the Yenisey River which flows from Tuva through Siberia and into the Artic Sea. Khovalyg improvised

over the music, whistling, trilling and cawing, using throatsinging techniques

to simulate birdcalls. At times the other members joined in with their own dove-calls, squawks and loon-cries. When the instruments dropped out for the last minute of the song, the effect was amazing: if you closed your eyes, you could imagine yourself on the banks of the Yenisey on a spring day, the singing birds carried swiftly by the brisk Siberian wind blowing past your face and over the steppe.

Khmei has been in use in Central Asia for centuries, both as social music for storytelling and as religious music for shamanic rituals. The music, like so many other cultural riches, was heavily repressed under Soviet rule, but has experienced

an enormous resurgence recently. “We still have shamans,” said Bapa. “It doesn’t have to end.” That spirit is quite apparent even in the music itself. “I kept getting chills,” said one concertgoer. “It was exciting.”

While Huun-Huur-Tu’s brand of Tuvan music is decidedly more authentic

than that heard in ethnobeat and in experimental projects like Bjrk’s “Med£lla,” some Western elements did seem to creep in. Bapa played a nylon-stringed guitar on two songs. He defended

this, saying that the music simply fit the instrument, and wasn’t Westernized at all. “I don’t have an Ionian scale,” Bapa said after the show. “It’s totally my scale.”

Steve Sklar, the man who maintains khoomei.com and is one of the few Westerners to have mastered the art, was also in attendance Saturday. He attributed

the West’s recent interest in Tuvan culture to groups like Huun-Huur-Tu. “They’ve been traveling out, beating the drum, and getting the word out there,” he said. When asked for advice for aspiring

throatsingers, Sklar said that it’s quite difficult. “Some people will be able to figure it out,” he said. “But people should go slowly. You have to build strength, go easy, and above all, use common sense.