Kaysera Stops Pretty Places was only 18 years old when she was reported missing by her grandmother in 2019. The call was ignored by law enforcement. Five days later, her body was found in a backyard less than a mile away from her reservation. Aubrey Dameron of the Cherokee Nation has been missing since March 9, 2019. Since she is a transgender woman, her family feels she may have been the victim of a hate crime. Grotesque as these cases are, they have received little to no attention from law enforcement and the media. Now, these women’s names, ages and stories are memorialized across campus on red paper dresses.

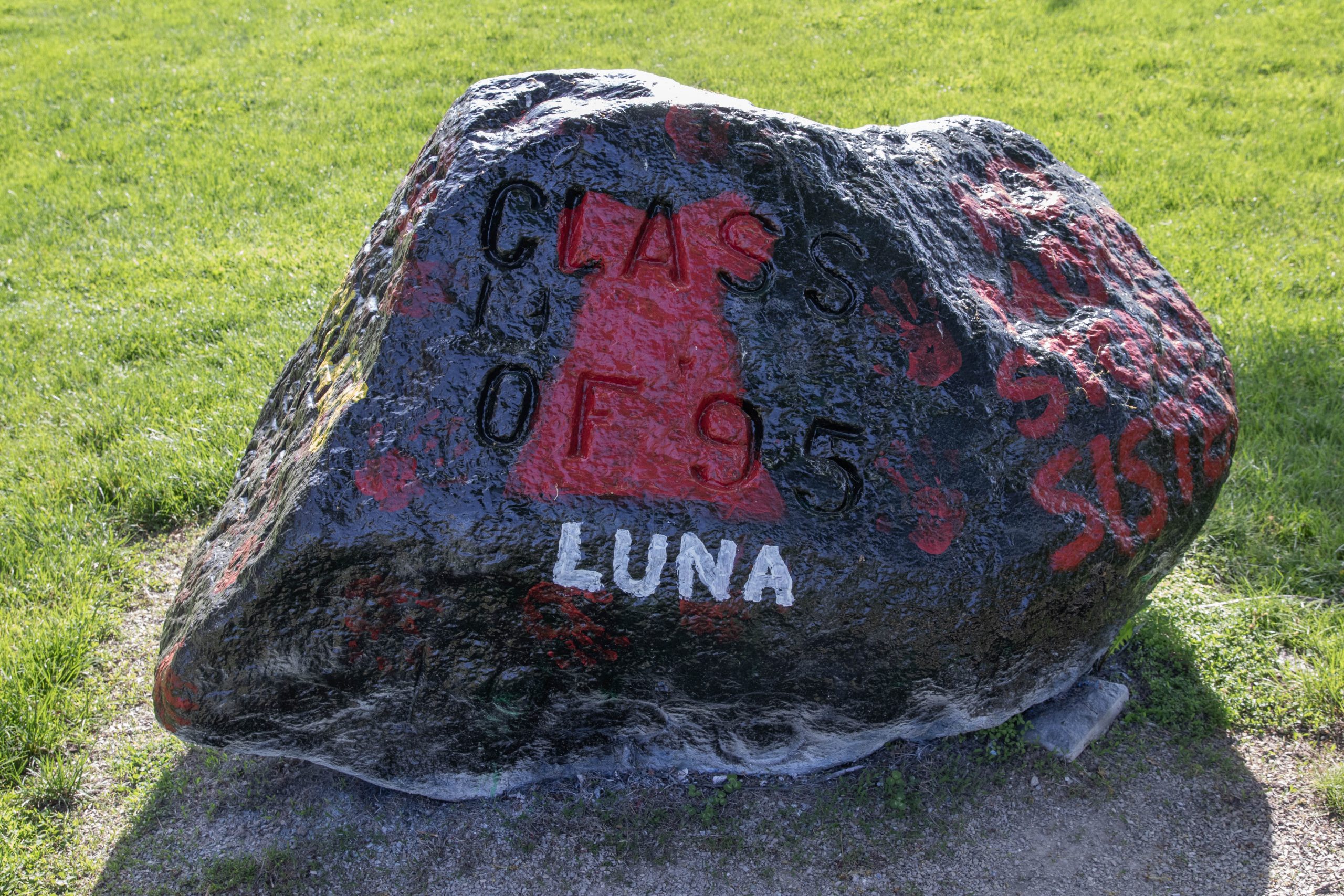

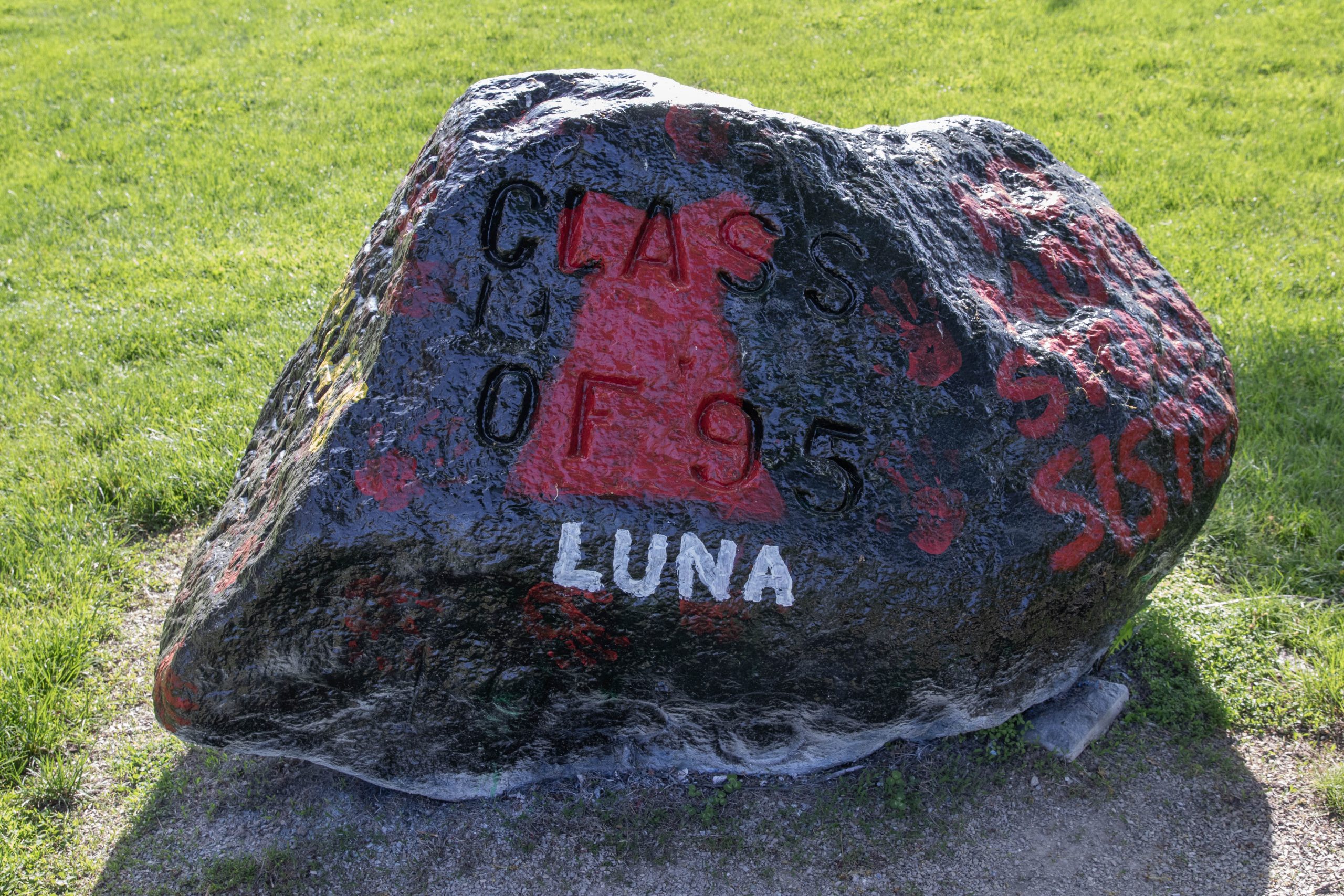

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) is a movement to foster awareness of missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls and Two-Spirit—an Indigenous gender identity with spiritual, cultural and religious significance—people. According to Lawrence University Native Americans (LUNA) president senior Mahina Olores, the movement began in Canada when a young Northern Cheyenne woman’s murder case was neglected by law enforcement, the media and the government.

Sadly, her case is far from the only one of its kind—murder is the third most common cause of death for Indigenous women, girls and Two-Spirit people—but they have gone largely unrecognized by the public. Olores criticized inaction from law enforcement as one of the ways that Indigenous women, girls and Two-Spirit people are still being taken and murdered. Without intervention of the law, families cannot get justice and perpetrators remain unpunished.

High school sophomore Isabella Ruston of LUNA also pointed to the institutionalized bias against Indigenous women, girls and Two-Spirit people to further explain law enforcement and media neglect of MMIW cases, especially due to institutionalized misogyny, colorism, featurism and classism. She feels that often, women are silenced or not taken seriously when they try to share their stories, and that this is especially true of Indigenous women.

“Oftentimes, we give white women or white feminine-presenting people the opportunity to have the spotlight for their cases, and we don’t really pay attention to [Indigenous women],” said Ruston.

As a result, many Indigenous people who try to reach out to law enforcement for help are ignored, and MMIW cases are left uninvestigated.

First-year Bailey Nez also attributed underrepresentation of MMIW to the legal “gray zone” regarding governments and Indigenous nations.

“A large portion of MMIW is a non-Native person perpetrating against a Native person, and when that happens, Native communities do not have jurisdiction over that,” said Nez. “If some random person comes in and commits an act of violence, there’s nothing they can do. And the state often won’t do anything because they have no jurisdiction on Native land. There’s this big gray area, and it allows a lot of these perpetrators to go unchecked and feeds into this idea that as […] an Indigenous woman, that you’re expendable, you’re disposable.”

The MMIW movement is represented by the red dress and the handprint, the latter of which symbolizes the silenced voices of MMIW and their communities. Red was chosen to represent the movement not only as the color of blood and earth, but because red has a deep connection to Indigenous culture; red is the only color that spirits can see. As a result, family members of MMIW often hang up their red dresses outside to call their spirits home, as well as to show how empty they look without their loved one in it.

Similarly, this is how LUNA is taking action to raise awareness about the movement. Members of the organization are collecting vignettes of unsolved or overlooked MMIW cases—some from years ago and some as recent as this month—copying them down on red paper dresses and displaying them around campus. Olores said his goal is to humanize these lost women, girls and Two-Spirit people beyond being just a statistic. By placing the dresses in places regularly busy with student traffic, such as dormitories and Warch Campus Center, he imagines that people will be more likely to stop and observe the people beyond the acronym. Nez said that to her, this project is all about raising the voices of Indigenous communities.

“We’re still here,” Nez said. “We’re not going to be silenced, and you can’t ignore us anymore.”

Some of the dresses have contact information and GoFundMe pages for family members of MMIW on them for another way to support them and interact with the movement.