Early decision by the numbers

The early decision practices of many colleges and universities were called into question in the Jan. 11 issue of The Chronicle of Higher Education. Some educators believe the admission option may be doing more harm than good.The early decision process came about during the 1970s, according to Lawrence’s Dean of Admissions Steven Syverson. Under this process, students apply to and receive a decision from their school earlier in the year than the typical deadline. If accepted, the student must withdraw all other applications unless the financial package presented by the school is unsatisfactory. The early decision option was originally implemented to relieve pressure for students who knew earlier than most which school they wanted to attend. The students would be under less stress knowing they had been accepted or that they needed to find a new school. However, early decision is not always what it seems.

“The reality is that early decision, in many ways, is self-serving on the part of colleges,” said Syverson. Because magazines like US News and World Report are becoming increasingly popular among applicants, it is tempting for schools to manipulate their statistics to make themselves look more selective. The higher their ranking, the better the school appears to be.

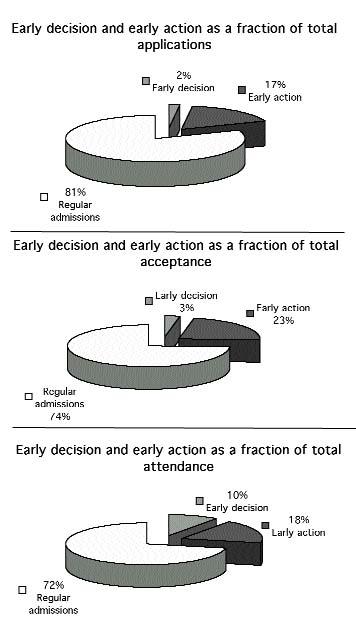

One statistic used to determine the selectivity of a school is the number of students who attend that school after acceptance. At Lawrence, early decision yields about ninety to one hundred percent in this category, whereas regular decision is a far lower thirty percent. For every one student offered acceptance in the early decision process, Lawrence would have to admit three under regular decision to get the same yield. “If I could admit less students and still enroll my class, then I will look more selective,” Syverson explained.

Certain schools are going to extreme measure to manipulate this statistic. According to Syverson, schools will wait list students that are normally acceptable if they believe the school only has a small chance of actually enrolling the student. For example, a student who is accepted at an Ivy League school and applies to a less selective college will most likely choose the more prestigious institution. Therefore, the less selective school, rather than offering admission to a student who probably will not accept, will put the student on a waiting list to keep their yield number high. “That kind of game playing just seems offensive to me. It’s the wrong way to go about this, but it’s partly driven by all these rankings and ratings. Colleges are trying to play the numbers game,” argues Syverson.

A number of schools also look at how much interest a student has shown in the school. If the student has visited the school, written to the school, or talked to an admission’s counselor are all ways they use to measure interest. Syverson says, “[some schools] will wait list the kids that are perfectly admissible, might even be at the top of their class, but that appear to not have been as interested. Again [it is] a strategy to protect their yield.”

Syverson says Lawrence does not look at interest and continued by saying, “a batch of us in the profession are really ashamed of what’s happening right now because we think that it’s not fair to students, it’s not appropriate, it’s the wrong way to go about making admission decisions.”

Even if the schools are not looking at interest, early decision pulls in large numbers of applicants. Some colleges are accepting as much as sixty to seventy percent of their freshman class on the early decision option. Syverson points to a weakness in the system saying, “That means there aren’t very many slots left for all the other kids. And the high school counselors are saying, ‘How many kids really honestly know in Oct. that this is really their first choice?’ They’ve still got six months of growing up to do. That’s a lot of time in a high school student’s [life].”

Syverson worries students pressured to apply for early decision may choose a school that does not fit their best interests. “There’s a sense of needing to apply early, not that I have a clear first choice. It has gotten very distorted in the last few years,” Syverson said.

There is also the concern of financial aid. Many schools claim to use more aid on their early decision students, leaving less for those who choose to apply regular decision. According to Syverson, this is not the case at Lawrence. “…[early decision] doesn’t affect [Lawrence applicants] at all because we don’t do anything different for early decision versus anyone else.”

Another admission choice that Lawrence offers and other colleges are beginning to offer is early action. It is similar to early decision, but the student is not bound to attend the school if accepted and the financial package is agreeable. It simply allows them to know ahead of time if they have gotten into the school of their choice, relieving pressure. Early action has been in existence at some schools for almost fifteen years but has become more common in the past five.

One of the newest admission options is instant admission. Under this option, students meet with the admission counselor of a college, present their transcripts and test scores, and take part in a brief interview. Students know if they are accepted at the end of the interview. Syverson says this is not something Lawrence is considering because they look at more than test scores and transcripts when admitting students, but added, “never say never.