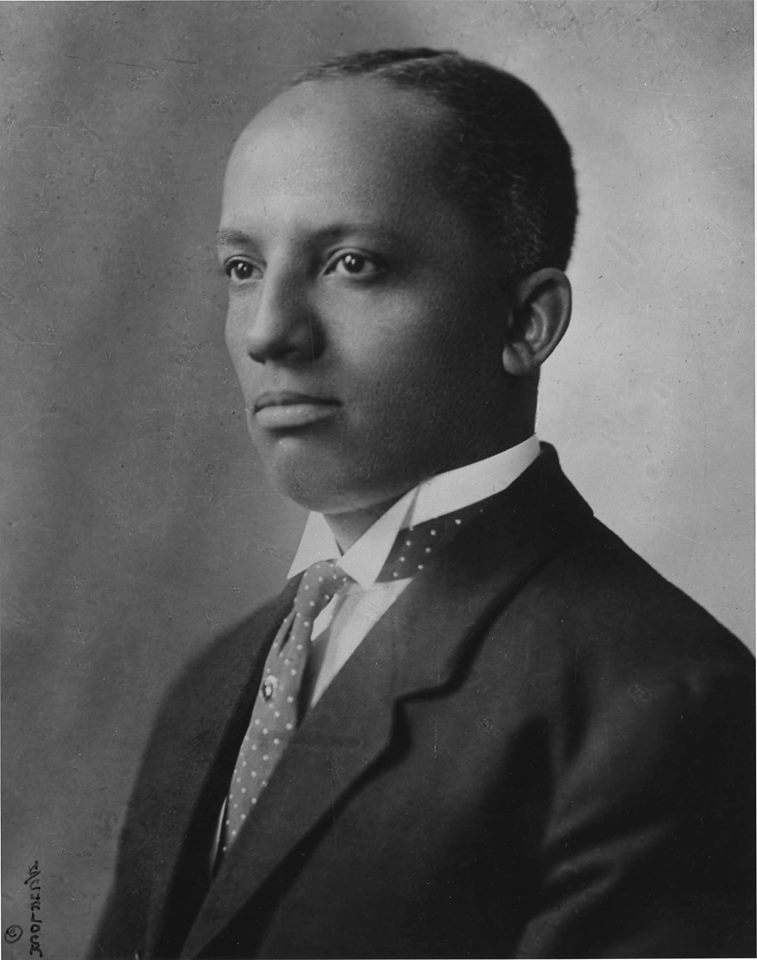

Dr. Carter G. Woodson.

Photo from Public Domain.

Black History Month (BHM) is celebrated in the United States from February 1 to March 1 annually. During Black History Month, also known as African American History Month, the lives and accomplishments of Black Americans are celebrated. It is also a time to reflect on their struggle and criticize harmful systemic racism and daily discrimination these very same people endure throughout their lives. BHM is a time to learn, ask questions, teach, listen and educate ourselves about the impact of these hurts and joys. For the month of February, an article will be published each week to illuminate Black history and the ways it has uplifted individuals, communities, peoples, democracy, the United States and the World. Black writers, photographers and artists are invited to submit their contributions to The Lawrentian as a feature or as an ongoing project. Your voices are important, and we want to hear them.

Black History Month was established as Negro History Week in February 1926 by Dr. Carter Goodwin Woodson, an African American author, historian, and journalist. The week was selected because it included the birthdates of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglas, two figures broadly acknowledged for their importance in African American history. The weeklong celebration stemmed from the organization that Woodson founded in 1915 as the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History which is still active today under a new name, Association for the Study of African American Life and History, or “ASALH” (Library of Congress).

Dr. Carter G. Woodson was born in New Canton, Virginia on December 19, 1875 to former land-owning slaves. Born into a poor family, he spent much of his youth laboring, driving a garbage truck and working in a coalmine. He attended high school and eventually earned his Bachelor of Law (B.L.) degree in 1903 at Berea College, Kentucky. During that time, he taught black youth in West Virginia. In 1908, he received a Master of Arts from the University of Chicago in history, romance languages and literature. He taught while earning his doctoral degree (Ph.D.) at Harvard University, completing it in 1912 (Black Past, Pero Gaglo Dagbovie). He was the second African American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University, following W.E.B. Du Bois.

Dr. Woodson changed his field and the evolving way we view American history forever. He was one of few of his time to be of the philosophy that Black folk had not been acknowledged for their contribution to society and that the world needed a better understanding of this (National Geographic, Erin Blakemore). In collaboration with historically Black fraternity, Omega Psi Phi, Dr. Woodson created Negro History Week with a hope that the short event could become something celebrated annually. Eventually, he felt the need to reach a broader audience with his celebration and thus worked toward making the event nationally recognized. The primary emphasis of doing this was to encourage a widespread, coordinated teaching of Black history in public schools (The Journal of Negro History, Carter G. Woodson). Soon he had the cooperation of the Department of Education, Washington D.C., Baltimore, as well as the state boards of North Carolina, Delaware and West Virginia. Historians note that the event not only examined Black history, but also celebrated literature, arts and music that have come from it (Making Black History, Jeffrey Aaron Snyder). The result is one of Dr. Carter G. Woodson’s most outstanding contributions, the establishment of Black History Month, which is now celebrated internationally in the United Kingdom (1987), Canada (1995), and Ireland (2010).

In addition to becoming known as the Father of Black History Month, Dr. G. Woodson was also a prolific writer, whose works inspired many young African Americans attending college to participate in the Civil Rights movement of the 1950s and 60s. Dr. Woodson established the scholarly publication Journal of Negro History in 1916, the Negro History Bulletin in 1937, and formed the African American-owned Associated Publishers Press in 1921 (Biography.org). He wrote eighteen books; among them are The Rural Negro (1930), The History of the Negro Church (1921), and The Story of the Negro Retold (1935). The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933), one of his most notable books, has become required reading at many universities and colleges (Berea College, Sona Apbasova). In honor of the impact, he has made in African-American history and in Black literature, there is a literary award named after him. The Carter G. Woodson Book Award, established in 1974 by the National Council for the Social Studies, is given to “the most distinguished social science books appropriate for young readers that depict ethnicity in the United States. The purpose of this award is to encourage the writing, publishing, and dissemination of outstanding social science books for young readers that treat topics related to ethnic minorities and relations sensitively and accurately” (Carter G. Woodson Book Awards).

Dr. Carter G. Woodson died in Washington D.C, on April 3, 1950, but his legacy lived on. At Kent State University, Black educators and student organization, Black United Students, proposed the extension of the week-long event he had established. The first Black History Months was celebrated there February 1969 and 1970 (Kent State University, Milton E. Wilson). Not long after, about six years later, BHW was celebrated in schools and Black communities across the country. On February 10, 1976 President Gerald R. Ford recognized Black History Month during the United States’ Bicentennial celebration (“President Gerald R. Ford’s Message on the Observance of Black History Month”).

Although this series of special articles initiated for Black History Month may only last a short time, we must extend the importance of Black history throughout the rest of the year. It is not enough to merely pretend to care about the visibility our Black and brown siblings for the shortest month of the year for the sake of “wokeness” or clout. This is a very real and nontrivial problem that has soaked American history in their blood and tears from day one and has not since dried up. Imperialist and racist erasure of an entire people, of African American people, is an unacceptable tragedy and should be an intolerable guilt. Speak up when you see this injustice. If you have privilege to make changes, use it. It is clearly not enough to just acknowledge the presence of another, let your actions reflect a love of your Black neighbor—and Black friends, love yourselves. This love will change the world.